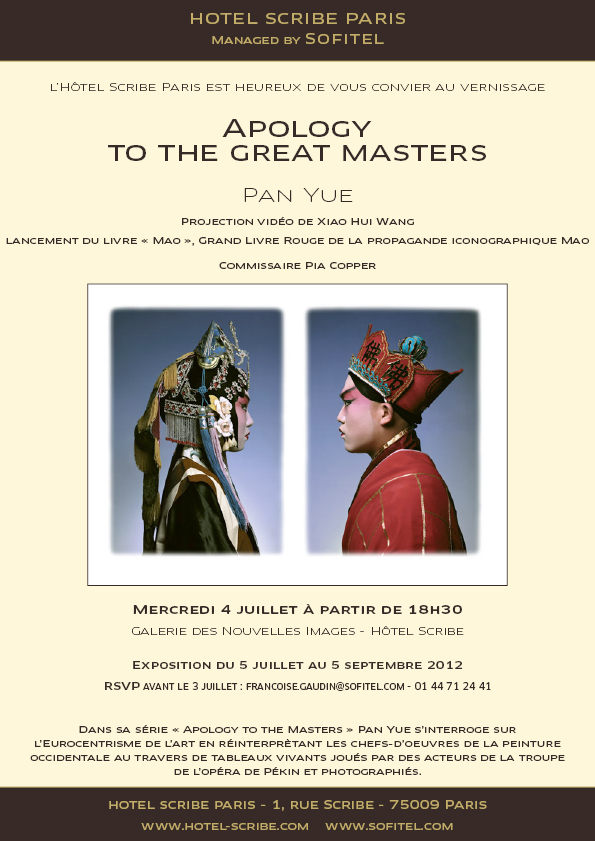

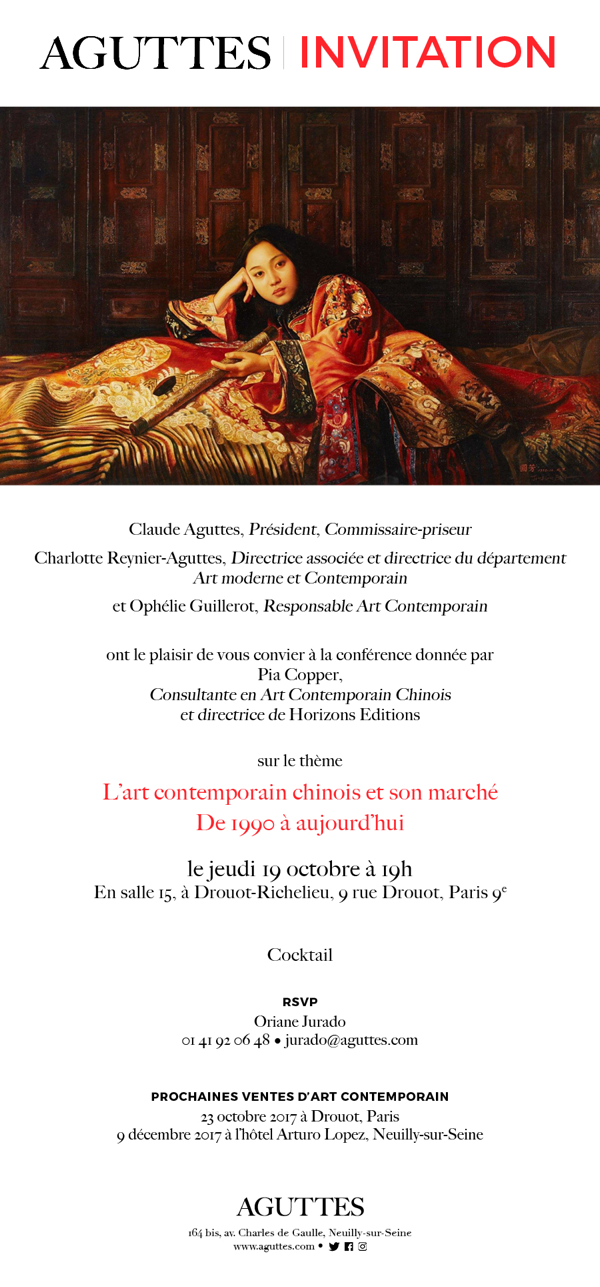

Art events 艺术活动

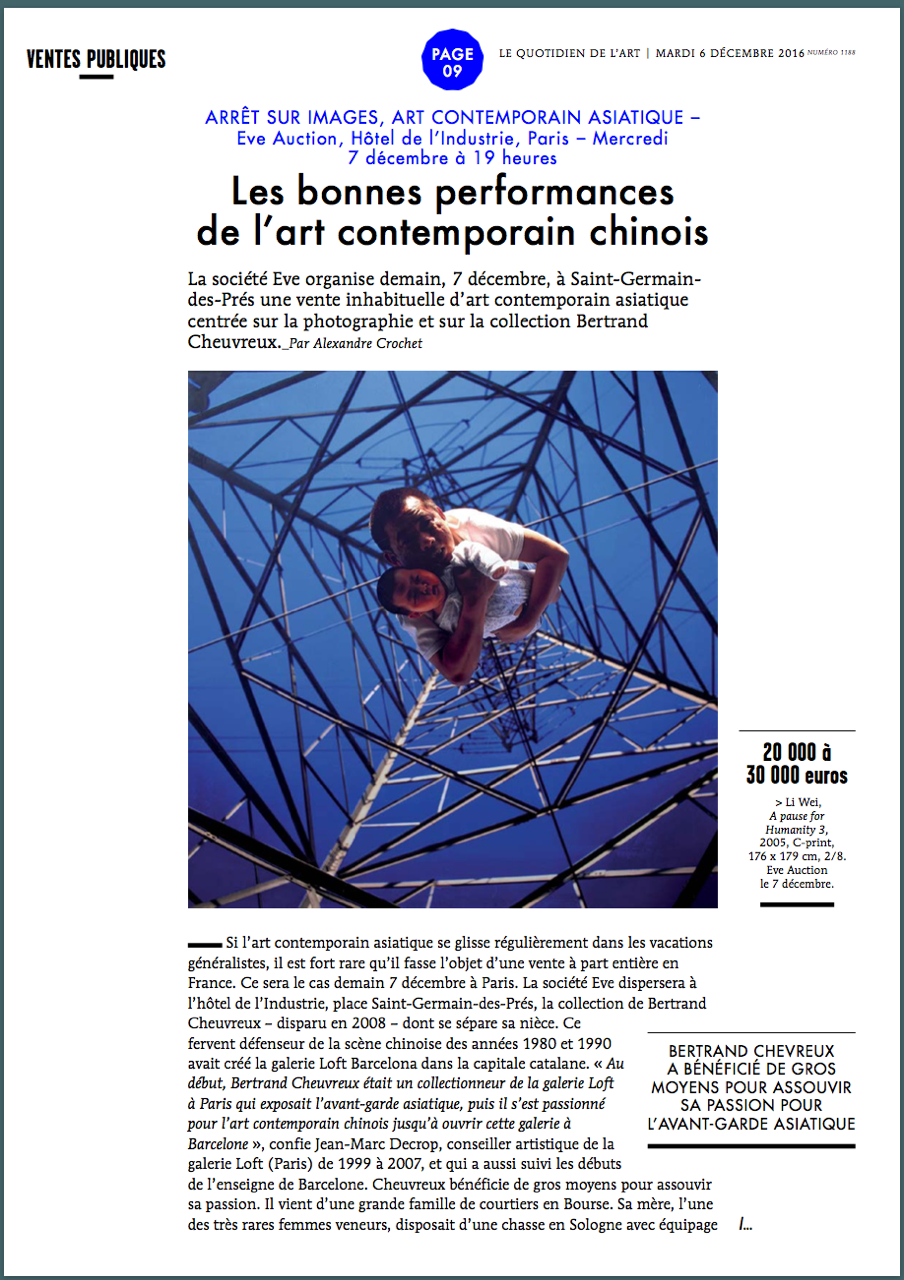

The China Click sale is the opportunity to revisit thirty years of Chinese contemporary art, in particular Chinese contemporary photography. The Cheuvreux collection is in effect nothing less than a summary of the history of photography in the People’s Republic.

The proceeds of the sale will go to finance a young artist prize and residency in the Loire valley in the Cheuvreux family domain.

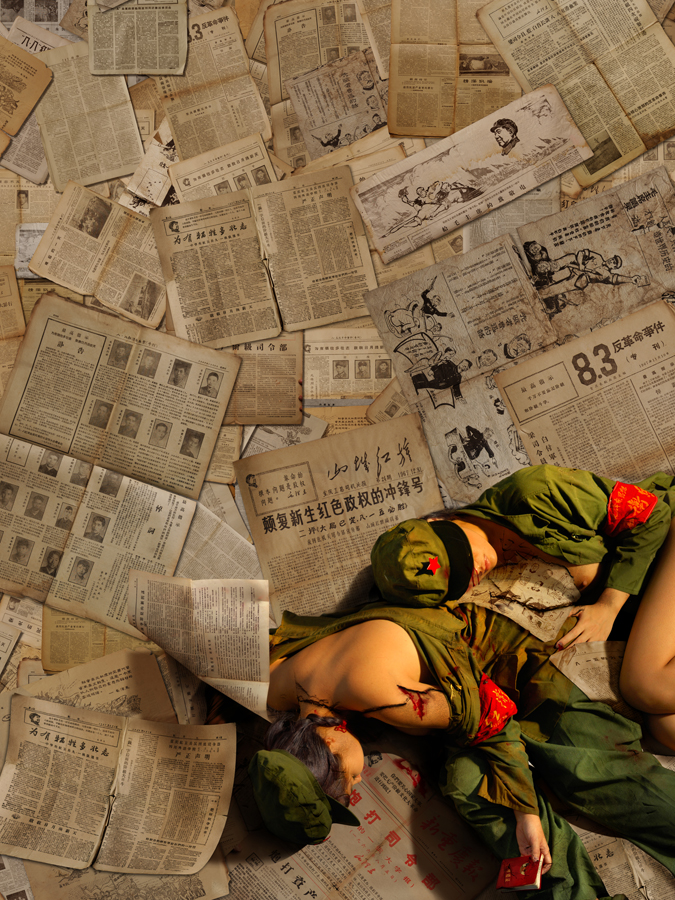

Rong Rong and his first clichés in the East Village, the first artists’ squat; He Yunchang, the most physical Chinese performance artist breaking out of a block of cast cementwith only a mallet, Cang Xin exchanging outfits and lives, or samsara, with people (jockey, artist, waiter, etc) in Barcelona “Identity Exchange,” and once more captured in the iconic "Trampling Faces" photos in which the artist tramples on his own plaster image, and then lets Ma Liuming, another East Village artist hold up the mask as photographed by Rong Rong, a sort of artists’ slight-of-hand. Chen Lingyang, the first feminist and revolutionary photographer, one of the only women, posing in Twelve Flower Months, a powerful, daring inditement of the power of the vulva.

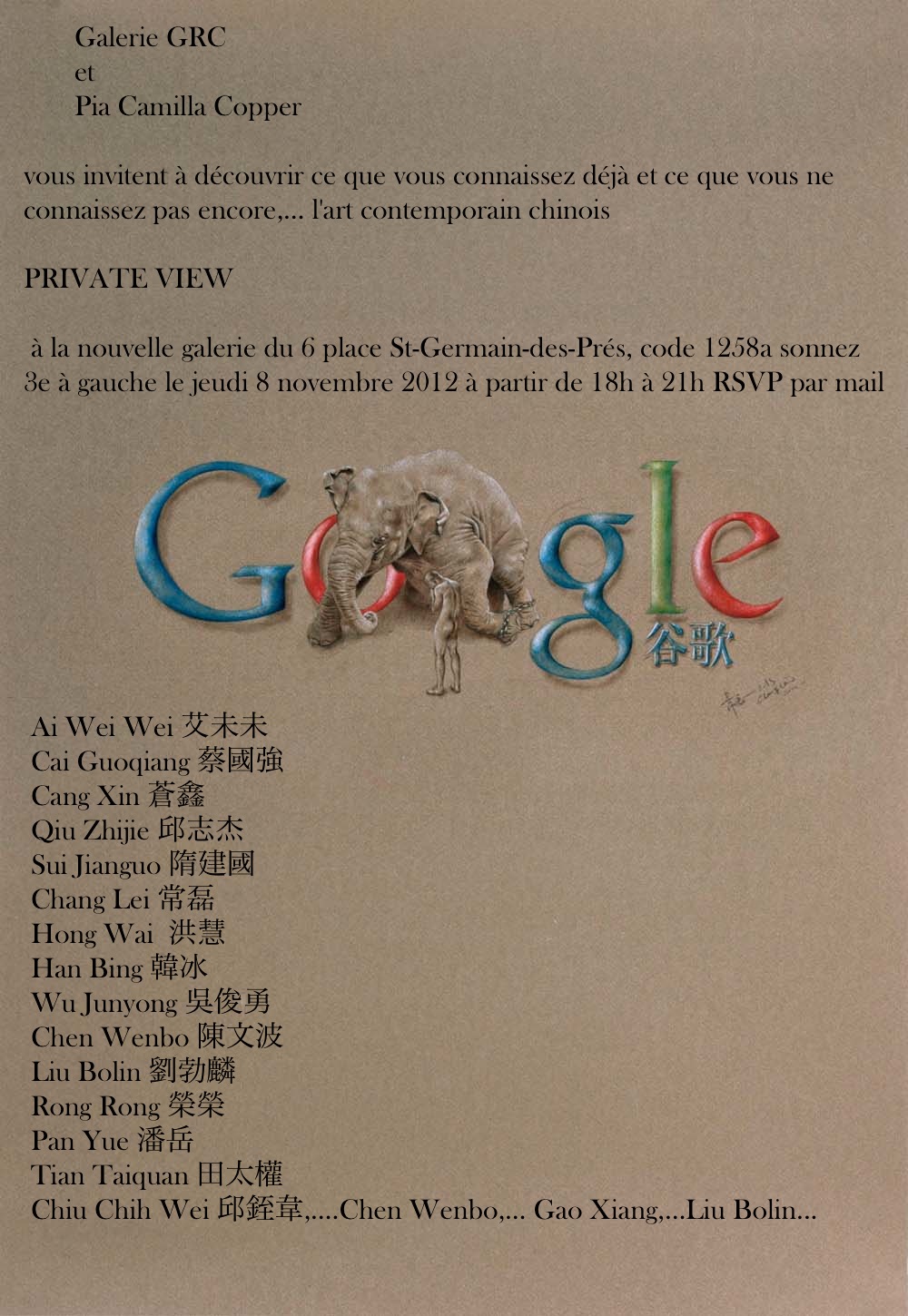

In this exhibition of photographs and charity auction, we also see the first conceptual clichés of Zhen Guogu, from the Guangzhou School, the clique around Vitamin Art Space and He An, a virulent critic of consumer society with his photographic montage and reworking of brand and fashion logos demonstrating the hypocrisy of the modern world.

Dai Guangyu, one of the New Wave pioneers, a poet and painter, drowns himself in an ocean of ink and water expressing the distress of the intellectual caught in the whirlpool of capitalism. There are also the first touching photographs of Liu Wei, the acrobatic performance artist who does his first works in Dashanzi with his wife and child, holding his swaddled baby held high above the Beijing skyscrapers.. many, many years before he suspends himself theatrically in Paris’ Grand Palais. How can one fail to mention the works of Han Bing who so lovingly embraces a bulldozer on the streets of Beijing, positing man against the machine, tradition against modernity in such a heart-rendering pose in which he puts himself at risk with police? The first photo-accumulations of Hong Hao, the first decadence photos of Wu Gaozhong, the photographic collages of Yin Yi, and the first machine photos of Zeng Yicheng. The history of Chinese contemporary photography is little known in the West and is worth a visit—at once one of the great manifestations of Chinese modernity and of a certain quest for identity.

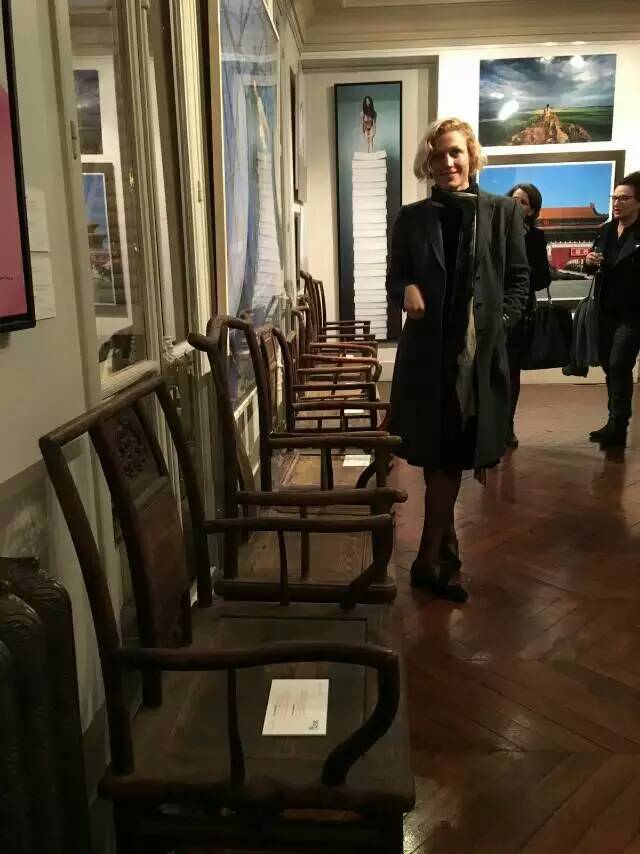

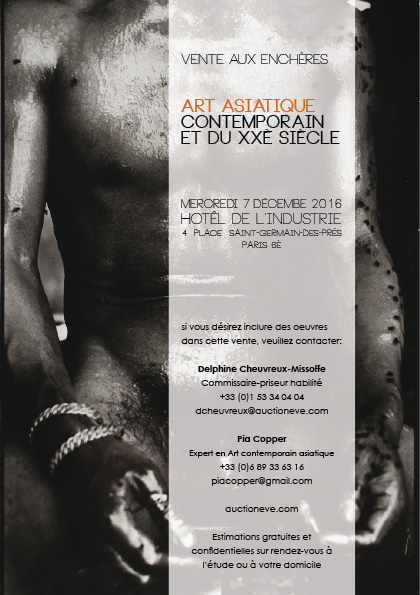

The prestigious Hotel de l’Industrie is located on Saint-Germain-des-Prés square in the very heart of Paris. It is here the Cheuvreux charirity auction and modern and contemporary Asian sale will be held on 7 December, 2016. The artworks will be exhibited in the sale Lumière and sale Chaptal from 3-7 December 2016. An opening cocktail will bring together the luminaries of the Chinese contemporary art world: collectors, critics, museum directors and amateurs on 2nd December 2016.

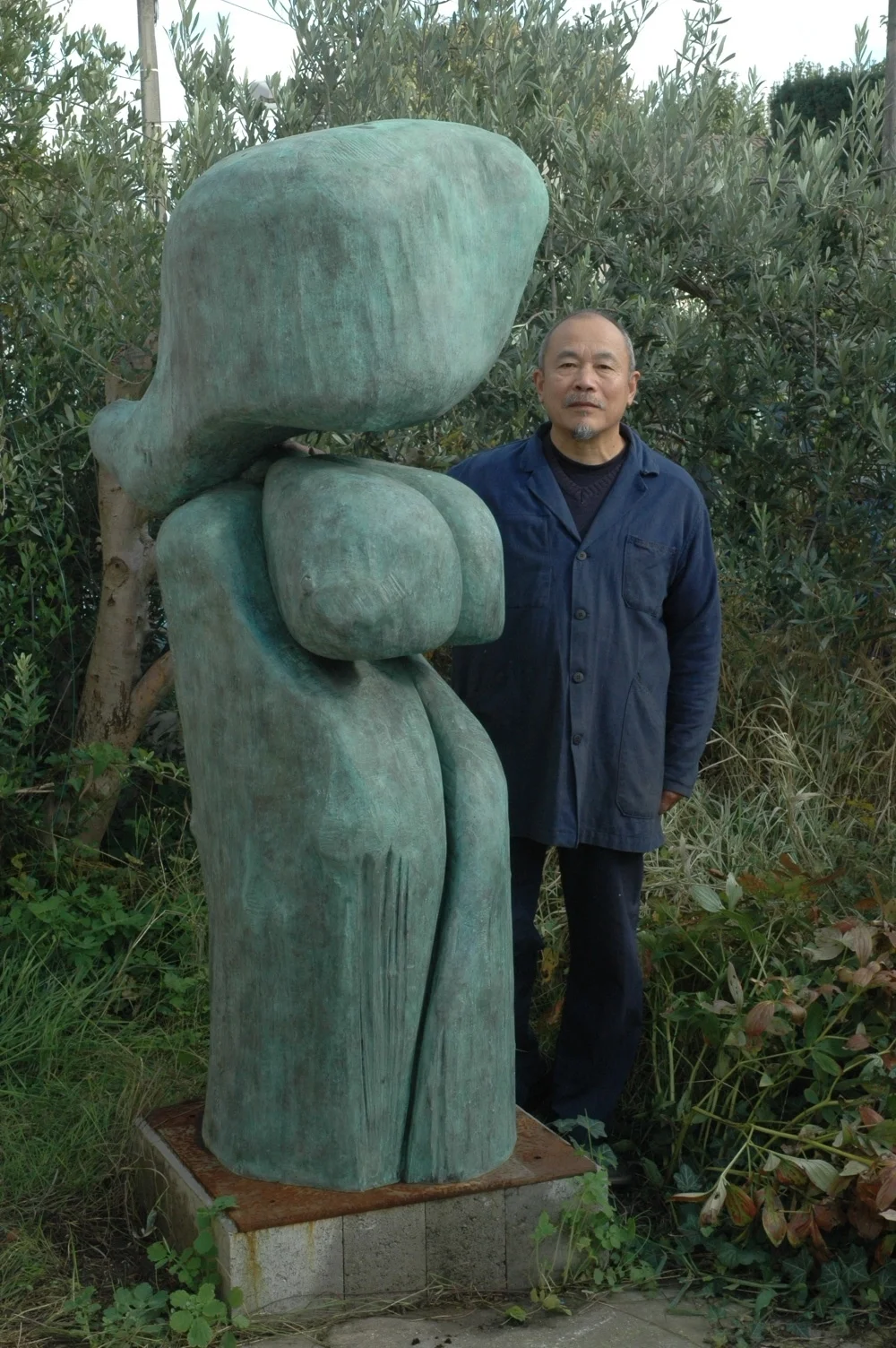

Cang Xin is known for his artistic performances, rethinking the relationship between man and his environment, both his cultural environment (The Identity and Exchange and Identity as a Tourist and Communication series) and the natural environment (Man and Sky series ). One of the founders of the East village, China’s first artist squat and one of the leading lights of the Beijing art scene, Cang Xin is also a painter and sculptor.

Rong Rong is one of the pioneers of Chinese contemporary photography, documenting the performances of his peers in Beijing East Village. His performances with his wife Inri were also iconic. His work allows us to understand more fully the modest beginnings of other artists Zhang Huan, Ai Weiwei and Ma Liuming. But more than simple records, Rong Rong’s photographs express the 90’s artists’ strength and radical outlook.

He Yunchang has the reputation of an artist used to extremes, using performance to push the limits of his own body. He had himself cast into concrete cube and then broke free, endured a operation democratically voted on, slicing one meter of his body from neck to thigh, and even immolating himself. He Yunchang is a political artist who uses violence to shock the viewer, part of the radical art politics of the early 90s.

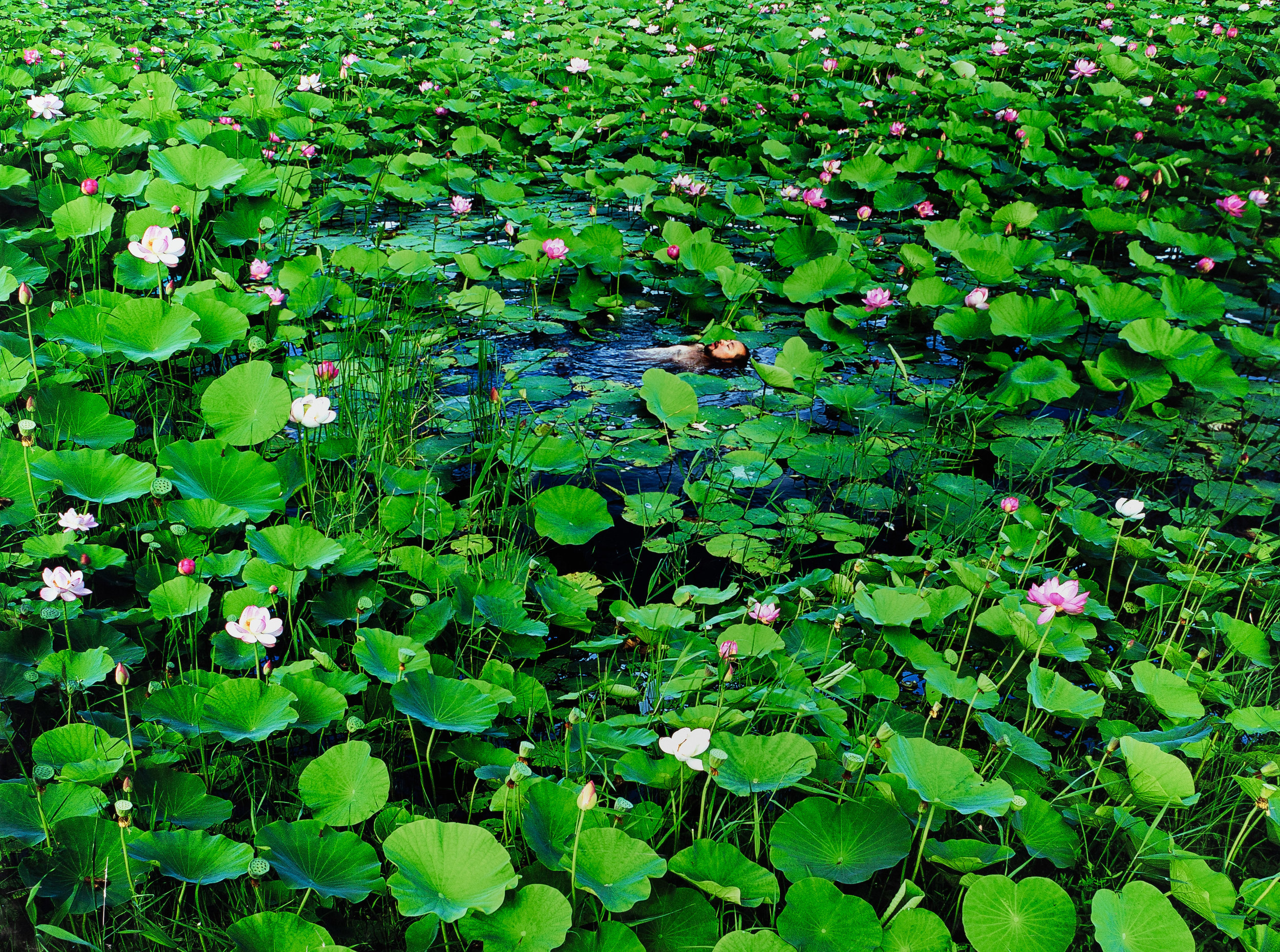

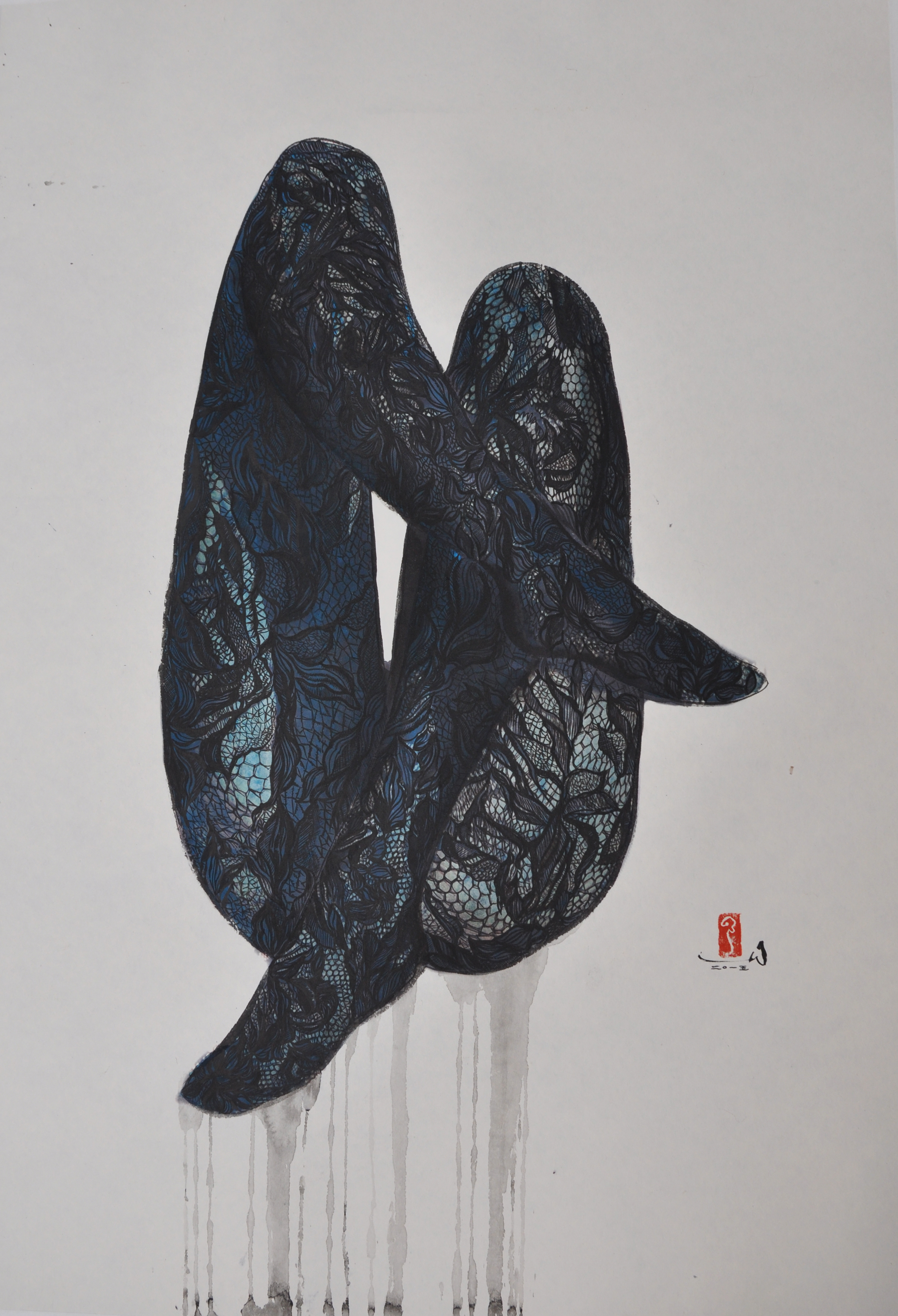

Dai Guangyu is a multi-talented artist (calligraphy, poet, photography, performance...), part of the 85 New Wave movement. His conceptual performances traditional Chinese ink and wash, generally limited to brush and paper. He lets ink seep into the ice of a lake, or drip from the roof of a courtyard house, or be painted on someone’s own body, he drowns himself in ink in a German lake, plastering his face white like a character from a Chinese opera. He is one of the most unconventional artists of Beijing today.

Li Wei is an artist world renowned for his acrobatic performances, defying the laws of gravity. Mixing performance and theatrical staging, his photos have a particular energy, they betray a lively creativity and express the humour and absurdity of contemporary urban life.

Hong Hao is a diverse artist. He works with digital photo montage to criticize a consumerist and superficial society. He is most famous for his series of accumulated daily objects («My Things», 2001), staged and photographed with great and minute detail.

He An is a politically revolted photographer. Usingphotomontage and painting to disrupt fashion and brand stereotypes, he criticizes the consumer society and the «Made In China» concept through his art.

Chen Lingyang is one of the first feminist artists in China. She reference Chinese artistic tradition of calligraphy and transforms it into a contemporary photographic work, a self-portrait of her menses, “Twelve Flower Months”. She uses an ancient Chinese form to question contemporary Chinese society and refocus on the themes of intimacy and femininity.

Twelve Flower Months associates genitalia with the traditional flower calendar questioning the taboo of the feminine genitalia and challenging views of the place of women in patriarchal China.

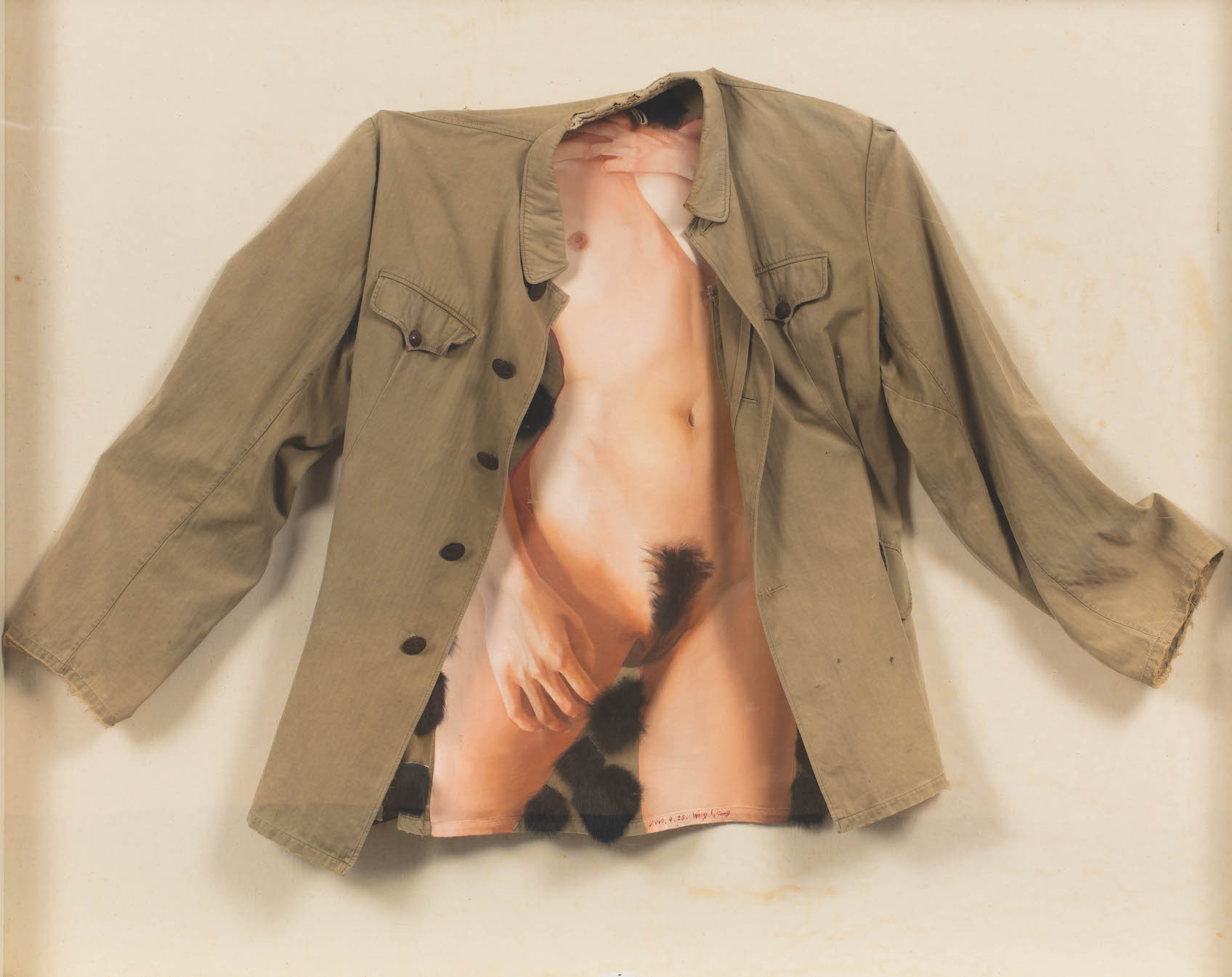

Wu Gaozhong ia part of an earlier generation of multi-talented Chinese artist (painter, installation, sculptor and photographer) in the entourage of the acclaimed critic Li Xianting. His work is more conceptual, like a Surrealist “maître d’oeuvre” for his generation. His Rock and Flower series recreates traditional ceramic gardenlandscapes with organic materials. Allowing them to decay and mould and become truly beautiful, he questions the idea of decadence and the fragility of life itself .

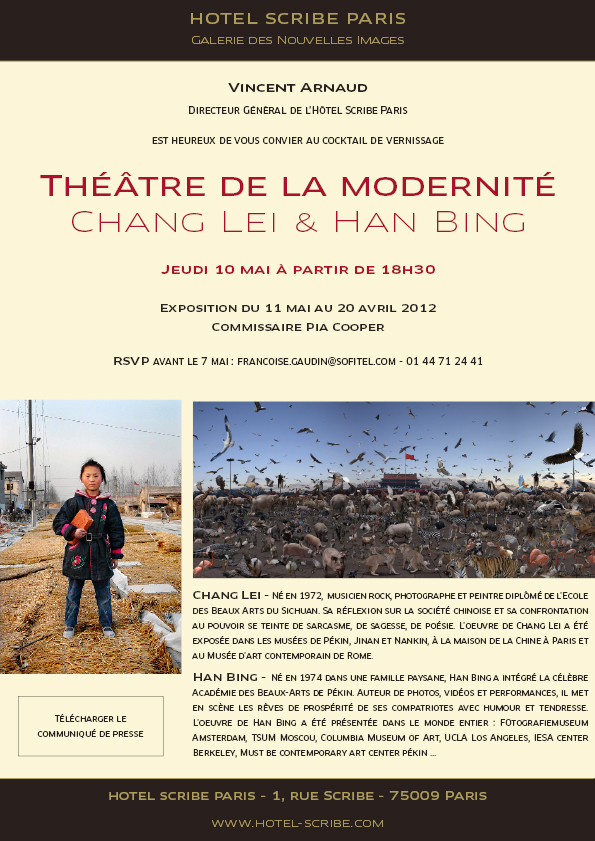

Han Bing is another of the artists of contemporary Beijing whose works is a cry against the inhumanity and the violence of contemporary society. His series “Love in the Age of Big Construction” done in Beijing during the demolition of the hutongs is a self-portrait with a bulldoze, positing man against machine, love against loss, humanity and tradition against modernity and soul-lessness.

Zeng Yicheng work has now changed focusing on more traditional landscape themes. However, his earlier work as a student of CAFA Beijing was interested in man and machine. This series “Man and Machine” questions the impact of Chinese industrialization on the individual and the loss of humanity in the modern age.

Arrêt sur 影像

中国现代艺术重点

BERTRAND CHEUVREUX 藏品 2016年12月7日 晚 7点正

展览 2016年12月3日 – 6日,11点- 7点

Hôtel de l’Industrie

4, Place Saint Germain-des-Prés, Paris

巴黎 - 中国当代艺术将在12月7日由Eve拍卖行在巴黎theHoteldel’Industrie, place Saint -Germain-des-Prés 举行。

这次拍卖的特点于Bertrand Cheuvreux藏品系列的历史系列,其收录了中国当代摄影史的五十幅举足清重的作品。Bertrand Cheuvreux画廊拥有者和收藏家,创办了巴塞罗那阁楼画廊,并与许多中国艺术家紧密合作,直到他在2008年去世。

此次拍卖还包括朱明,赵武基,唐海文,广义,艾未未,郑国谷,荣荣,王克平,毛旭辉,邱志杰,隋建国等重要艺术家的作品。拍卖的另外一个亮点是推介中国新一代现代艺术家:英吉,王林,蔡东东,张磊,更包扩新艺术媒介,卡通艺术家李超雄和李昆武。

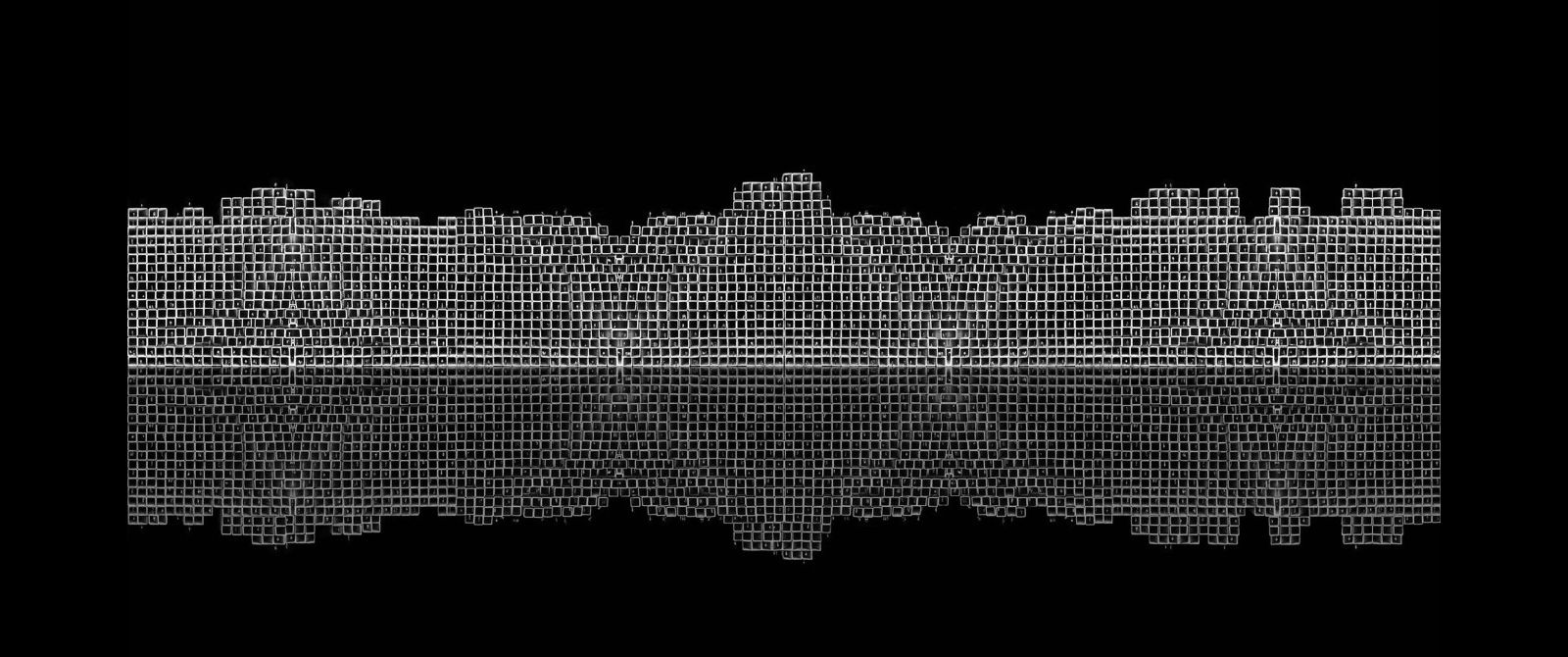

拍卖的重要作品之一是艾未未于2007年在德国卡塞尔现代艺术展会展现的十张椅子,一个名为《童话》,由1001张椅子组成的大型行为艺术的一部分,艾未未從自己的博客中募集了一千零一位中國人参于其中。这个社会政治“现成”的艺术行为因其高昂成本已震惊了整个艺术界:《童话》是艾未未在2007年德国卡塞尔现代艺术展会的400万美元项目一部分。

每张《童话》椅子均有编号,售价从1至2万欧元不等。

中国当代艺术场景在这次拍卖会上呈献了其所有的活力和创造力,展现了1990 - 2000年间中国当代艺术在其高峰期最重要的一批艺术家。

拍卖将巴黎的Hôtel del’Industrie的卢米埃尔大厅 (Lumière hall) 举行, 此大厅原为电影院,卢米埃尔兄弟 (lumiere brothers)在此首映了他们的第一部电影《工廠大門》(La Sortie de l'Usine Lumière a Lyon)。

BERTRAND CHEUVREUX 系列

中国当代摄影和中国行为艺术的历史在西方是鲜为人知的。 Bertrand Cheuvreux 系列丰富了我们的视野,并展现了该时期的一些标志性的历史照片。

巴塞罗那阁楼画廊创始人和收藏家Bertrand Cheuvreux(1953-2008)是90年代中国艺术家的殷切信徒。 他在中国花了几个月与艺术家建立友谊,并且想将他门的作品呈献给西方。

某些作品体现了这种共谋:沧行的身份交换系列-艺术家在巴塞罗那的一个行为艺术表演,由阁楼画廊赞助,在那里他与西班牙城市的居民交换身份拍摄了一系列照片。

阁楼画廊还导演了一个标志性表演“践踏面具”的再制作,在那里,艺术家将自己脸上的面具碾压在脚下,重现何云昌的作品:铸 Casting。

.由荣荣拍摄的“东村第一张照片”,由何云昌演出,沧行著名的身份交换系列和陈灵阳的女权主义革命系列《十二花月》等,很多Cheuvreux 收藏系列现在被认为是艺术史的一个重要组成部分。

我们还呈现诗人和行为艺术家戴光宇的“墨水游戏”,韩冰的“大建筑时代的爱情”系列,艺术家将自己赤裸身躯与摧毁北京古老胡同的推土机对立 ,吴高中的“腐烂的水果,腐朽的风景”,英怡的有趣的拼贴画“城市风景“, 等等。

FDCA:现代艺术发展基金会

FDCA于2007年由Bertrand Cheuvreux创立,目的是推广中国现代艺术,并在西方培养更多了解中国现代艺术的欣赏者。 FDCA至力奉行 Bertrand Cheuvreux的目的,促进和传播中国艺术,使其能够在欧洲广被认受,并与旧大陆建立联系。

中国现代青年摄影奖

大奖为将此次拍买收益资助一位年轻的中国(或中国籍)摄影师。 一众蓝筹股艺术家一向垄断欧洲的中国艺术市场,中国现代青年摄影奖旨在搜寻和资助能逆转这一趋势的年轻人才。

该奖项将于2017年10月颁发, 地点容后公布。

邱 节 韩冰 艾 未 未 常 磊 谷 文 达 鲁飞飞 吴俊勇 洪 慧 高翔 张 洹 何云昌 戴光郁

Cang Xin Chang Lei Dai Guangyu

Gao Brothers Gao Xiang Gu Wenda

Han Bing He Yunchang Hung Tunglu

Lu Fei Fei Wu Junyong Zhang Huan

with the launch of Ai Wei Wei’s book Ai Wei Wei-isms

Chinese artists have always been considered “zhishifenzi” 知识分子, “men with thunder and lightning at their heels”. They have always been the critics, the moral safeguards of society. Restrained yet spurred on by dictatorship, artists in China have never waivered, insisting on talking about the real issues such as massive urbanization, the one child policy, the legacy of Mao, the overwhelming burden of propaganda on people’s lives, the imprisonment and exile of dissidents such as Ai Wei Wei. Others have decided to go beyond politics, and adress issues of spiritual fulfilment and love. Perhaps this ever so subtle shift is part and parcel of the modernization China is undergoing, the artist themselves have changed, focusing inward to a new reality, the relaity of the self. This exhibition attempts to give a bird’s eye view of the Chinese contemporary art landscape, a glimpse into what artists or as they used to be called « the literati »are thinking and feeling in the Middle Kingdom.

In the past ten years, China has undergone transformations more overwhelming than twenty Western-style « industrial revolutions ». The Confucian family structure has been dismantled, Buddhist doctrine has been let go, old architecture and temples have been bulldozed to make way for a unstable future, an edifice built too quickly and structurally unsound. Even the essence of the original Communist ideal, that of a people’s republic seems to have been lost, making way for a capitalist/Communist mélange, a breeding ground for corruption, inequality and injustice.

In the aftermath of the Sichuan earthquake in 2009, Ai Wei Wei, criticizing the flimsy constructions of schools that left hundreds dead, many children; installed a wall graffiti at Documenta made of children’s backpacks that spelt out: “She lived happily on this earth for seven years.” His statement has far reaching implications, questioning the state’s responsibility in the disaster, endangering himself in the process (his online list of the dead leading to his incarceration) and daring to make a political statement using art. Ai Wei Wei’s book of changyu or proverbs, the little black book, are to present-day China what Pascal’s Pensées and Voltaire’s Lettres philisophoques are to Europe.

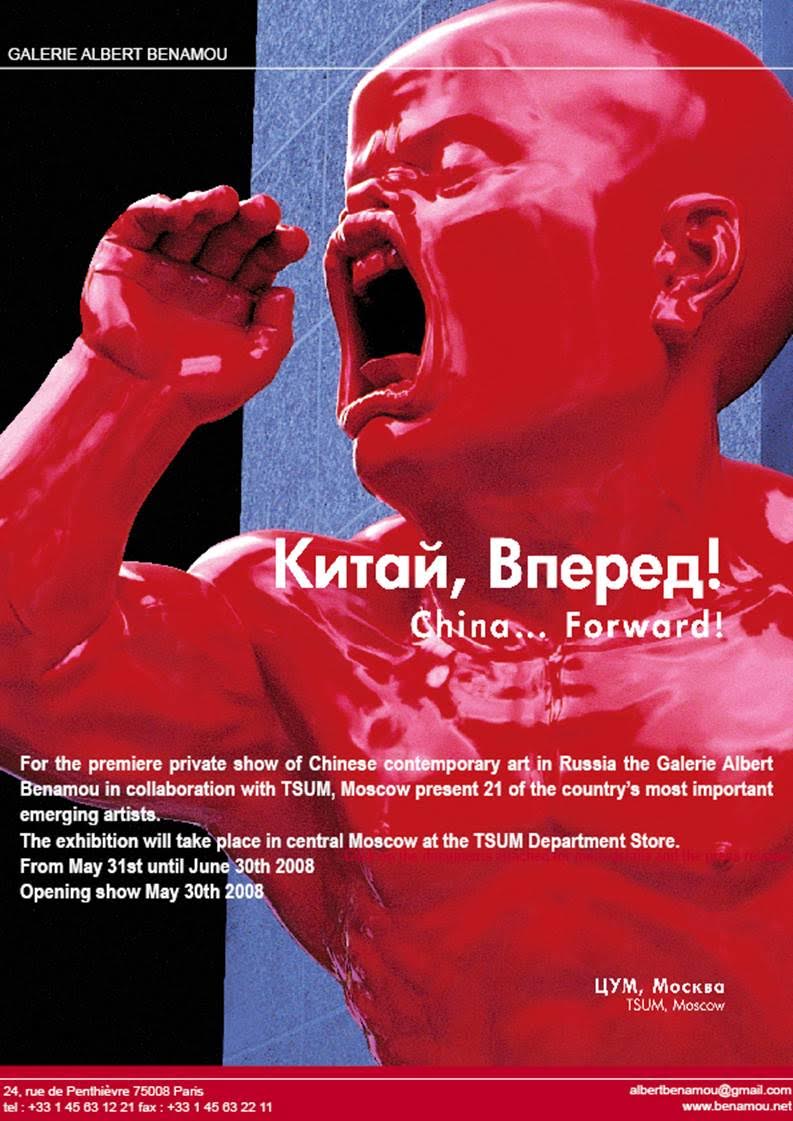

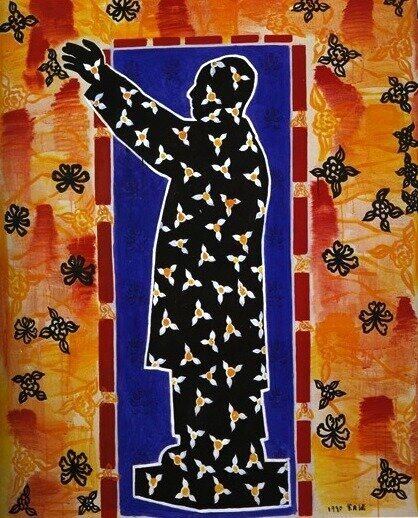

Other artists are just as bold. The Gao Brothers’ Miss Mao, which parodies the “Great Leader” representing him as a young voluptuous girl with a long braid and voluptuous breasts, has been forbidden in China. Several Miss Maos, or Mao xiaojie, also a derogatory term referring to courtesans and prostitutes, have been confiscated en route to international exhibitions. The Gaos are artist dissidents, a new breed born in the post-Mao era. Criticizing Mao is still paramount to treason, fifty years after the birth of the PRC, twenty years after his death. Miss Mao is to China what Warhol’s Brillo Broxes are to America, a reflection of the subconscious of a nation, subliminal perception.

Chang Lei, a former “yaogun” or rockstar is also not of the faint-hearted. His “Animal Farm” photograph has also never been exhibited in China. The Forbidden City features as a gigantic Noah’s ark, with all of China’s Communist leaders and army generals watching an unreal scene taking place in front of them on Tiananmen Square, a strange meeting of animals, seemingly chaotic and agitated, with Chang Lei’s naked body as the center of depiction, his hands held over his ears, like in Edward Munch’s scream. Animals tend to gather when there is a storm coming, unknown chaos and uncertainty, revolution. Chang Lei’s dreamlike digital creation is ominous.

Chang Lei’s series on propaganda, featuring pictures of young children next to the calligraphy of Maoist leaders, Deng Xiaoping through to Jiang Zemin, points to the impossible weight of propaganda, shaping generations of people and molding them forever.

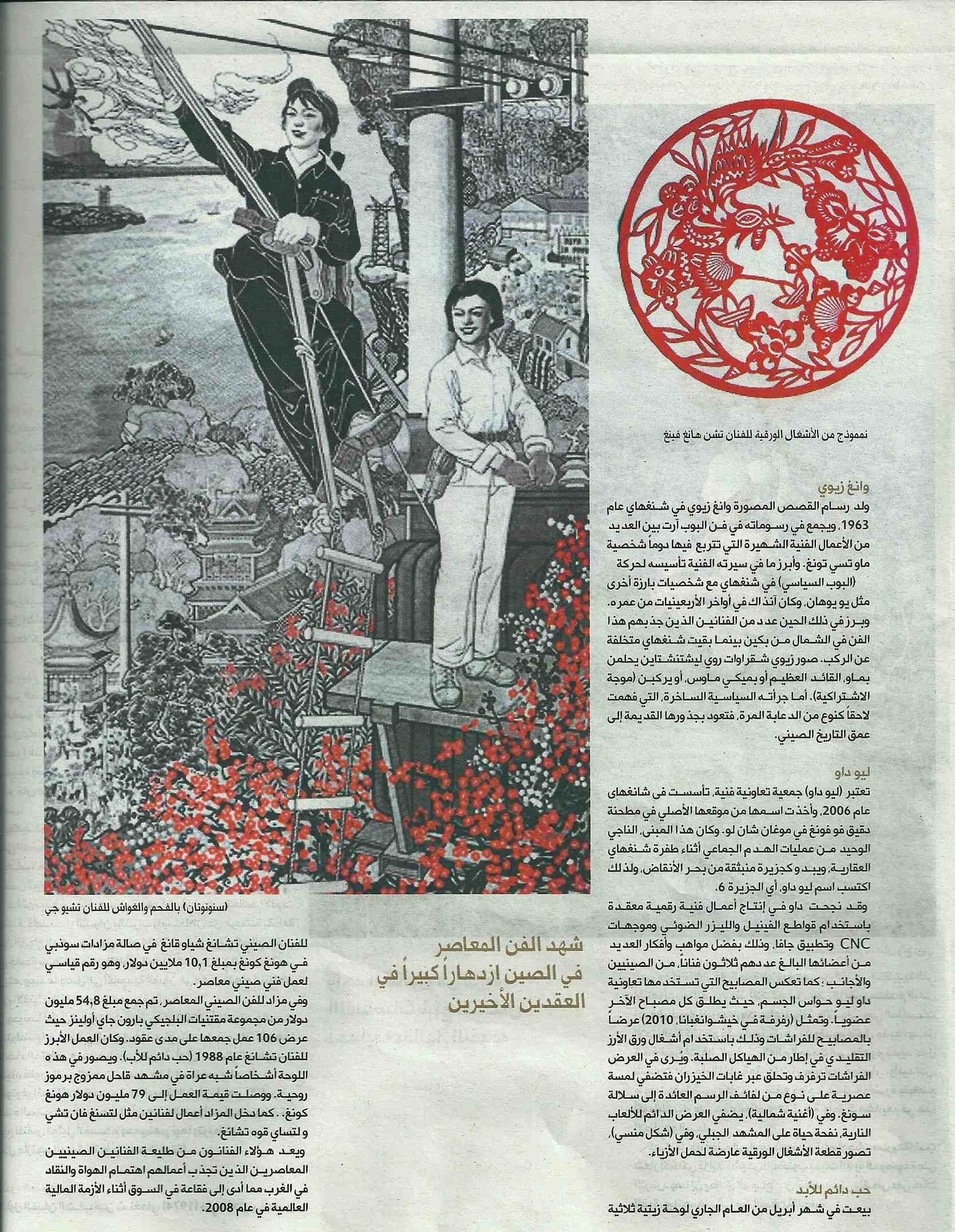

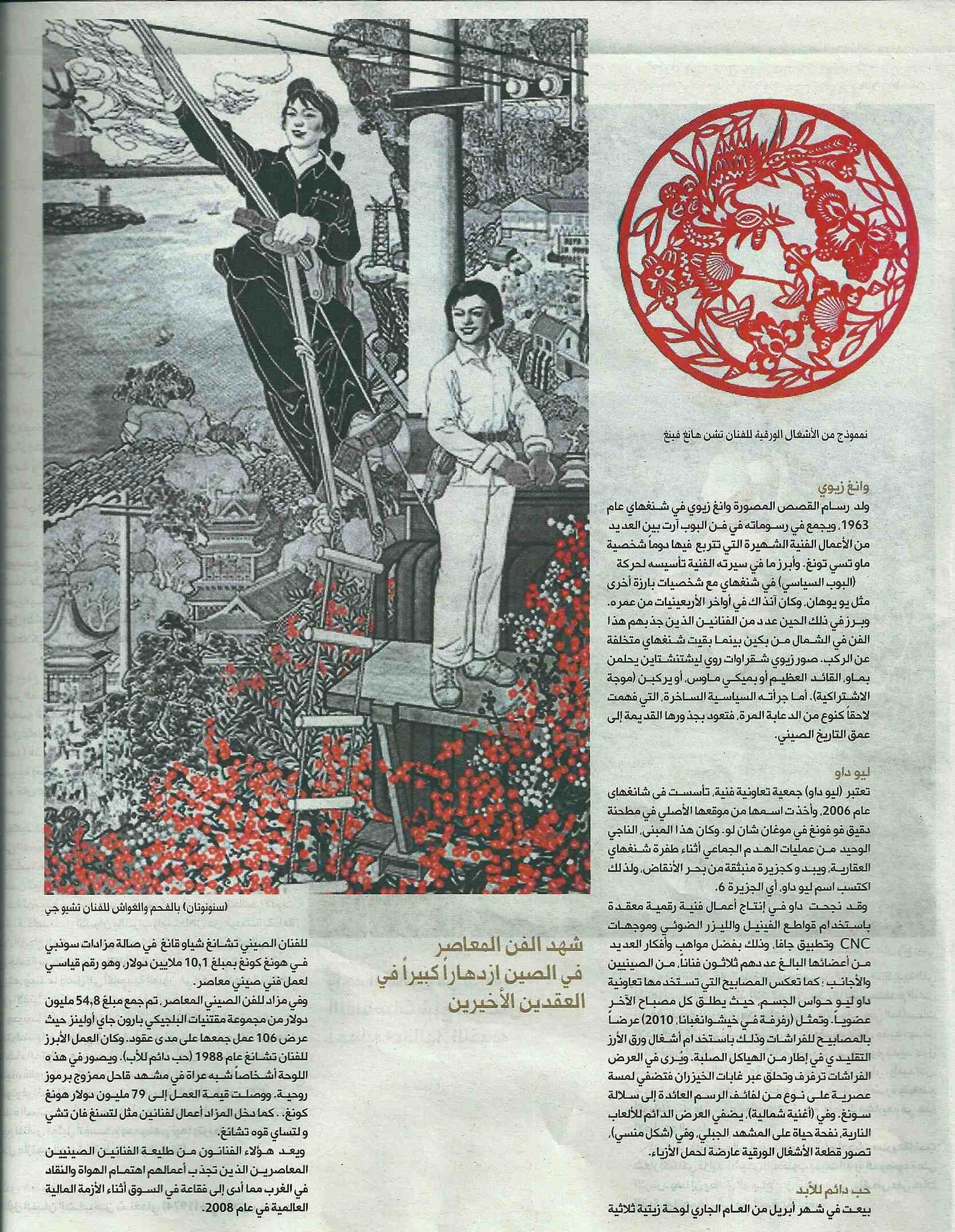

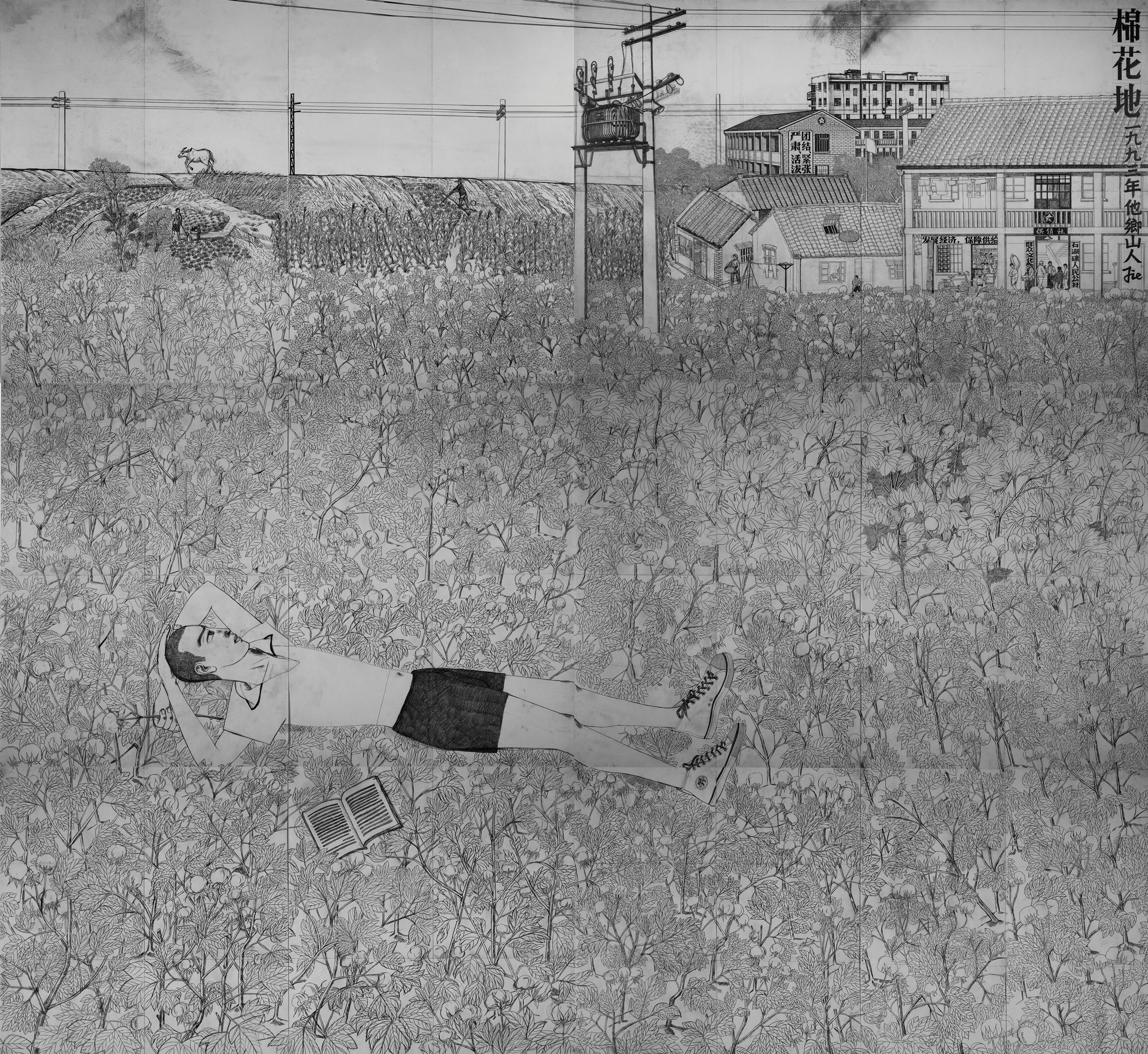

Qiu Jie’s “Woman and Leader” as well as “Two Swallows” points to the humorous side of “political pop”, growing up with Marxist-Leninism and loving/hating it. His large scale pencil drawings called dazibao or “propaganda posters”set the scene for a childhood on the Yangtze, traditional life in the teahouses, gardens, of old Shanghai, echoes of the past with acrobats, majiang games and dumpling vendors but with Communist heroines lording over it all, such as the femme fatale or the woman electrician. The backdrop to his childhood reveries and life are the sleeping giant, politics.

Wu Junyong’s video “Cloud Nightmare” is a masterpiece of a master paper cutter, the desuet Chinese art. Yet he uses the most cutting edge medium, video to make these characters come to life. Wu’s characters are brainless politicians, spouting useless propaganda masqueraded as Chinese mythology. They “call a stag a horse” as the Chinese say and the stag, appears and re-appears, a motif in this dream sequence. The men, who look like the Communist party cadres, convened at the People’s Congress, advance like blind men leading the blind. They sit on wobbly palanquins. Wu’s dragon is on fire, a taboo in old China where dragons are always considered immortal.

Lu Fei Fei’s young girls in her photographs, are a mirror of her own experience. She was one the many “elder sisters”, undocumented children, unregistered either as residents or in school because their parents desired a boy. She denounces a cultural practice that has made her obsolete.

As for He Yunchang, Ai Wei Wei’s clique, his performance using his body as a tool to test democracy speaks for itself. The incision practiced on his body, one meter for democracy, voted on by friends, is chilling and very real. The scar is still visible years later in “Ai Wei Wei bikini” in which he poses with nude models, all wearing the dissident’s face on their private parts. ‘The government opposes pornography and politics, why no do both?’ the artist states.

Dai Guangyu is also part of the first generation of Chinese artists, the Chinese “new wave”, who started creating around the summer of 89. A calligrapher and poet, his work bring the traditional aesthetic into the contemporary realm. “His Landscape on Ice”, shanshui and fengshui are part of a performance he did in Germany and China, reminiscent of the technique of the Buddhist and Taoists who use water to paint ephemeral poetry on the stone slabs of temples and palaces. Dai Guangyu’s ink paintings on ice, will disappear when the spring comes, creations reflecting the impermanence of sensorial experience.

Cang Xin, one of the founders of the East Village with Zhang Huan and Rong Rong, the first artist squat outside the Yuanminyuan palace, has never been one for too many words. As an shy art student, he found it difficult to communicate and instead decided to start a series of works called “Communication” licking things with his tongue. If he could not speak, he felt, he must enter into some sort of dialogue with the universe or people.

Later, his work assumed a shamanistic side. Cang Xin decided to posit himself as the shaman, intermediary between the universe and man, the ultimate role for the artist. In doing so, he also re-asserts the power of the individual in a society where all egos are crushed to make way for the collective consciousness. Cang Xin, wears an amulet of his own face, his shaved head, distinguing himself as an artist

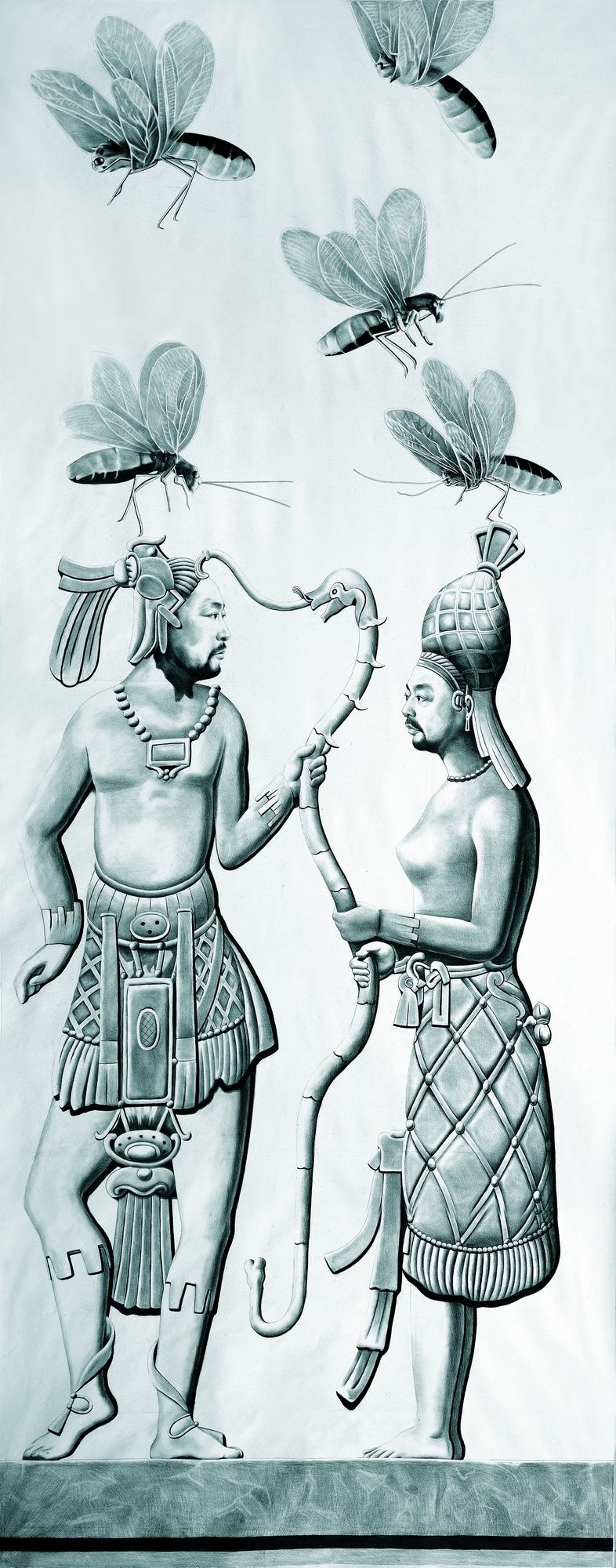

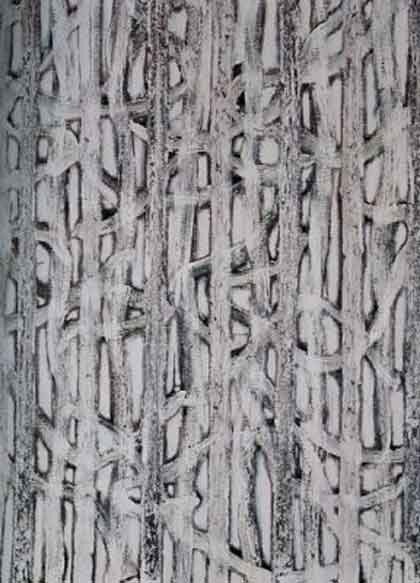

His giant Chinese-style scrolls in pencil are a self portrait, the artist becomes a demi-god, sitting cross-legged, in a Buddhist position, on the back of a qilin, a Chinese unicorn (identified by its scaly skin, dragon’s head), symbol of happiness and good fortune and a tortoise, symbol of Chinese longevity.

In Han Bing's "New Culture Movement" photo series, laborers, old people, and even school children, stand in front of the camera, like peons in a chess game, a red brick in their hands reminiscent of the little red book.

It is ironic that these villagers still believe in the Maoist dream of a brick house for all. In a China where glass and steel skyscrapers have overtaken the landscape, the rural working classes are lagging centuries behind the city dwellers. Han Bing did not set up these photos, the people he took photos of, are plainly and almost naively speaking of their dreams and aspirations, clinging to an ideology and a culture that has been left behind in the rush for modernization. They have no notion of what the modern era holds.

Hung Tunglu’s three-dimensionalmanga Buddhas printed on hologram paper stand for the spiritual, religions that have been stamped out in the global rat race. Having studied Renaissance art and the Madonnas of Bellini and Giotto, Hung Tunglu is fascinated by the meditative power of icons. His Buddha which moves as one approaches and moves away, allow the audience toreach the higher meditative plane, escape from reality and the world of suffering and temptations.

The video art of Waza Collective, Anonymous, Cao Fei, Hong Wai, is part of the new generation’s struggle to analyze the present. Hip hop, illegal surgeries, nuclear winter, are all part and parcel of the harsh Chinese reality.

In this respect, Gao Xiang’s red bride is a sort of postface to the exhibition. The little man in a Mao blue jacket is the artist himself, a toy prey for his muse and romance. The title, sardonic, is about freedom of the individual, as much as human freedom: “Who is the Doll?”

Pia Camilla Copper

Curator, Like Thunder Out of China

CANG XIN CV

born in 1967 in Heilongjiang

one of the founders of the Yuanminyuan East Village squat with Zhang Huan, Ma Liuming, Rong Rong and others.

part of the 1995 performance of bodies piled nude on top of one another “Add a Meter to an Anonymous Mountain” in Beijing

extremely timid, spoke very little as an artist so decided to do performance and even a communication series where he licked all things, animate and inanimate, in order to engage in a dialogue

a shaman

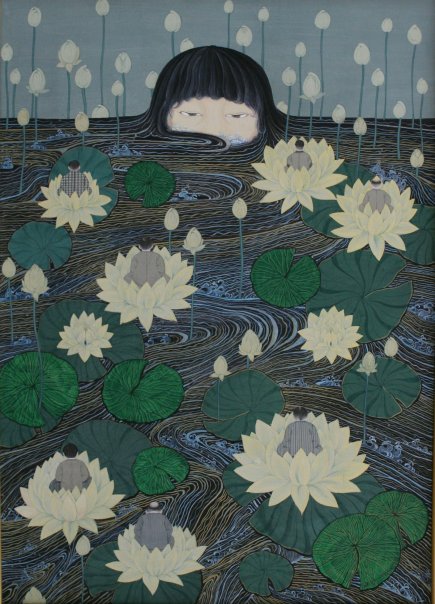

has bathed with lizards, worn other people’s clothing“to get into their skin”, lay on icy glaciers, and bathed in lotuses all to become an Other

sculptor, photographer, performer, painter, draftsman

the only one to speak the language of spirituality in China today

went to Tianjin school of music in the 1980s

autodidact

He has participated in exhibitions such as “Between Past and Future: New Photography and Video from China” (Seattle Art Museum), “Between Past and Future: New Photography and Video from China”, the David and Alfred Smart Museum (Chicago), Museum of Contemporary Art (Chicago) and the First Guangzhou Triennale, Guangdong Museum of Art, Guangdong, “Charming China”, (Bangkok Museum), “Chinese Contemporary Sotsart”, (The State Treyakov Gallery, Moscow), “Spellbound Aura”, Taipei Photography Museum of Contemporary Art, “Virtual Future”, Guangdong Museum of Art, “Hong Kong Chinese Contemporary Photography Exhibition”, Hong Kong Art Center, “Chinese Avant-Garde Art in the ’90s”, Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, Today Art Museum, the Zhu Qizhan Museum, Red Mansion Foundation, “Zhuyi!” at La Vireinna, (Barcelona).

Cang Xin, on the subject of his giant scrolls, November 2012, interview by Pia Camilla Copper

When did you become an artist?

I consider that I became an artist (a performance artist) when I first arrived in the “East Village” district in Beijing in 1993. Before then, I had only had a slight experience of different art practices from outside of China. I have to say that I did not have a clear idea about art at that time until Ma Liuming, Zhang Huan and I met up in the East Village and started doing performance experiments.

Where did you go to school?

I first when to school in Tianjin studying music and lyric-writing. But that was not a very satisfactory experience, thus I moved to the visual arts and started painting.

Where were you born?

I was born in in Baotou, a city in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of the People's Republic of China.

Which part of China influenced your work the most?

I would say Inner Mongolia, the place of my ancestral origin. This is the source of my later fascination with shamanism.

Are your scrolls inspired by Mayan art?

Yes, partially Perhaps, the Chinese civilization and the Mayan civilization are very much interconnected We do not know how close China has come to South America

Why represent the artist as a god? To destroy old gods? Or to counter ideologies like communism?

The artist is not god but the representation of a shaman, a medium between the gods and humanity; they have nothing to do with destruction and communism I am just representing myself as a shaman.

What does this say about your relation to the universe?

In ancient Eastern spiritual belief systems, all things have spirit, ling, and humans are merely a part of this big system There is no boundary between life and non-life – they are interchangeable, but that requires a middle person – a medium – a shaman to engineer this exchange so that an un-inhibited crossing (flow) can take place freely through the physics of time and space, and in turn maintain the perfect harmony of the universe as a whole This series of drawings is to humanize the medium, the middle person, and in due process to represent my own individuality.

Why do you often represent yourself? as an affirmation of the individual?

My whole art practice springs from my performance art Performance art uses the artist’s body to express artistic concepts, so these works [drawing series] are traces of the way in which I understand my own body, and they are also an affirmation of my own body and my own identity…

How do you do you do these gigantic scroll drawings, on a scaffold?

These works were made with the paper laid flat on the ground and drawn in a crouching position

Why the use of traditional scroll?

Because this way of presentation pertains to a certain Eastern aesthetic and Chinese tradition.

DAI GUANGYU CV

born in in 1955 in Chengdu, China

lives and works in Beijing, China

part of New Wave 85 Chinese art movement

calligrapher historian father

autodidact

calligrapher, painter, photographer, performer

invented “ink games” submerging himself in, eating, drinking, shooting at ink and drawn on, recomposed, thrown away and repasted ink paintings

has done extreme performances such as “Incontinence” (2005), “A Sheep Lecture on Chinese Contemporary Art” (2007)

His works have been exhibited and collected by Duolun MoMA (Shanghai), Louisiana Museum, (Humlebaek, Denmark) Guangdong Museum of Art, Chinese Arts Centre (Manchester), Macau Art Museum, China Millennium Monument Art Museum,National Gallery, (Kuala Lumpur), Hong Kong Art Commune, Mantova Museum (Italy), Faust Museum, (Hannover), Chengdu Museum of Modern Art and at such historic exhibitions as “China!” (Museum of Modern Art,Bonn),”The First Biennale of Chinese Art in the 90's” (Central Hotel, Guangzhou) and the first ever Chinese contemporary exhibition, “China Avant-Garde Art Exhibition”in 1989, subsequently held at Chinese National Art Gallery, Beijing.

Dai Guangyu on his ice calligraphy, January 2013, interviewed from Beijing

When did you execute the first ice calligraphy or shanshui (landscape)? How do you do them?

“Landscape ink on ice” was executed in the winter of 2004 in Germany and “Geomancy (Fengshui) ink on ice” was carried immediately afterward, on some frozen lakes in Beijing.

Chinese characters are written with ink on the icy surface, and over time, with the changing of seasons, they vanish before our eyes, and along with them the meaning, which they carry, vanishes. Through this performance, I want to point to the ephemeral nature of things, fragility of all that which is. Only if we are able to treat these basic realities with an undisturbed mind, can we understand the nature of all things, the basic fabric of life.

Why is calligraphy so important to Chinese culture?

Snow, ice and the Chinese characters, together, allude to Chinese culture; they become part of a cultural landscape.

As an example, geomancy, or feng shui, in the original sense of the term and its connotations, when set against a background of snow and ice, evokes the relentlessness of change in nature, the inconstancy of all which is. Through this, I want to express the certainty of the aleatory, which is beyond the influence of human willpower - all this belongs in the thought system of the I Ching or Book of Changes.

To write characters with a specific sense/meaning with ink on ice, then to watch them transform until they have vanished entirely, there is a lot of depth in this experience.

You have made a number of important performances in China, can you explain them and their importance to your way of thinking. “Incontinence” (done in 2005 at 798) featured you white-faced and in a business suit hanging by a noose in gallery holding a chicken. The second “Floating Object” (2006), saw you immerse yourself in water, dressed in the same way, business suit and white paste on your face.

“Incontinence” and “Floating Object” were executed around the same time (or at least there was not much time between their execution). They express, on one hand, the system of capitalist privilege (the first), and a sense of mourning of cultural loss, drainage (the latter). Both works contain very strong political allusions. The chicken in “Incontinence” represents China (we say the shape of the Chinese map resembles a chicken); the identity of the drowned man in “Floating Object” is deliberately left indistinct, because in reality, it is just as anonymous, it is just like that.

Formally, the inspiration for “Floating Object” is taken from the painting “Ophelia” by the Pre-Raphaelite painter John Everett Millais. But the drowning Ophelia still remembers her lover, and sings as she drowns, whereas the drowned man in “Floating Object” is drifting diagonally, not singing - but deprived of all sign of life; this is the state of Chinese culture today.

QIU JIE CV

Born in 1961 in Shanghai

Went to Shanghai School of Decorative arts and Geneva Ecole des Beaux Arts

Founder of the political pop art movement I Shanghai with Yu Youhan, Liu Dahong

Lives between Shanghai and Geneva

A romantic Blaise Pascal who recordsjournal of daily life in his drawings,

the tea he drinks, the music he listens to, etc

Works on giant dazibao pencil drawings meters high for months at a time

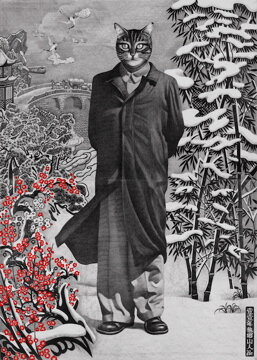

Invented the “Mao” cat making fun of the homonym

Prefers small-format oils

Has had solo shows at Shanghai Museum MOCA Show (most recently December-January 2013),

Arario Gallery, Hanart Gallery Hong Kong;

Has participated in famous shows such as “The Revolution Continues”, Saatchi Gallery

(London), “Borderless” Shanghai MOCA , Discover-Rediscover, Rath Museum (Geneva),

solo show on now (December –February 2012-13) at Shanghai MOCA,

Museum of Contemporary Art, Basel (with Ai Wei Wei)

Qiu Jie on his dazibao drawings, September 2011, interview by Pia Camilla Copper

Describe what the Two Swallows dazibao means to you? And the Mao cat?

“The Two Swallows” represents two Chinese working class heroines They are so capable, they can almost fly!

As for the Mao Cat, mao in Chinese also means cat So, this drawing is either the president or a cat! Whichever you prefer! The drawing is a play on words and a game at the same time

Why would you say your art is controversial?

As an artist who has lived in Europe for twenty years it is evident that my work is controversial in China and also in Europe where there is a cultural divide I am not a ‘real’ Chinese; but I am also not a ‘real’ European My home is in Geneva and my studio is in Shanghai My drawings bear the signature of a man with two identities I sign my work “the man who comes from the mountains”

What are some of the common themes you touch on in your work?

The common recurring themes in my work are the confrontation between cultures, East and West and nostalgia

Can you tell us how your childhood and the Cultural Revolution in particular has informed your art?

I think that our generation of artists is deeply marked by the influence of the Cultural Revolution There will always be a moment when we, as artists, touch upon this subject because it is a part of our history, our childhood and our experience

Do you, as an artist, still feel scared to express yourself under the watchful eye of Chinese authorities?

Over the past ten years the government and government controls are loosening One can always exhibit in private galleries But in state museums, it is still quite strict and controlled There is however still room to negotiate and discuss exhibiting works

What about China and your culture makes you proud to be Chinese?

Five thousand years of history and Chinese characters: I am very proud that such an ancient culture is coming to terms with modernity. It’s like a very old tree growing new branches and buds.

How would you describe the China of the future?

Very uncertain A lot of problems linked to rapid development As a Chinese person, I want the errors to be rectified The first issue is the environment because a centralized Communist state can develop grandiose things that have never been done before But the reverse side of the coin is that these things can have an impact on the equilibrium of the planet we live on But I have hope for my country and that enthusiastic hope is that they find innovative solutions for the future.

GAO BROTHERS CV

Gao Zhen 1956 Born in Jinan, Shandong

Gao Qiang 1962 Born in Jinan, Shandong

pair of artists brothers based in Beijing

doinginstallation, performance, sculpture, photography works and writing since the mid-1980s.works are exhibited and collected by Kemper Museum Of Contemporary Art(Kansas), Centre Pompidou, (Paris), The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Princeton University Art Museum, Wall Art Museum,Beijing. TSUM,Moscow, The State Tretyakov Museum (Moscow), Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art (Thessaloniki), Victoria and Albert Museum, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, The David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art (Chicago), He Xiangning Art Museum (Shenzhen), Guangzhou Art Museum, National Gallery & Chinese Pavilion (Albania), the Espace d' Art Contemporain of La Rochelle, Fukuoka Art Museum, and the National Art Museum, Beijing, China.

What is the significance of Miss Mao?

In the sculpture Miss Mao, we see a bizarre image: Mao’s sacred image as the leader and as a great man in Communist Party propaganda and within the collective memory of the people has been altered, from an idol into a funny doll which has the nose of Pinocchio, the pigtail of a Manchu lord, the breasts of a young woman, This work exposes the truth that Mao’s politics are a lie. Miss Mao is the irony of Mao and his system and the people fooled by Mao’s politics.Miss Mao has been exhibited all over the world and attracted the ire of the Chinese authorities. It has been blocked and confiscated several times by Chinese customs. Our studio was forced to be closed to public because of Miss Mao.

Why the giant canvasses of OBL? OBL has always been a very mysterious public figure. Although he frequently appeared in newspapers, magazines, on television, the internet and other media, our knowledge about him has always remained limited. We aim to inspire people to delve into the real nature of bin Laden. What kind of person was he? How was his childhood? How did he turn into the person we all know today? How big are the differences between the bin Laden reported by the media and the real bin Laden? And what kind of impact did he really have on the world?”

HAN BING CV

born in 1974 in Jiangsu

often features himself in his work, self portraits

began drawing in the dirt with pieces of broken glass, because his family could not afford

art supplies

studied oil painting in college, then to the prestigious Chinese Central Academy of Art.

In Beijing notices the gulf between the rich city and poor countryside

photographer, video artist, performer, painter, sculptor

has “walked the cabbage” in LA, NY, Paris, Shanghai, Beijing, Tokyo, San Fransisco,

Oakland and beyond

Han Bing answers questions, December 2012, interview Pia Copper

How did you come to be an artist?

I have been drawing since I was three years old, so I think I was an artist fromthe beginning even before knowing there was such a thing called “artist”.

Where did you go to art school?

I studied in a local university near my hometown in Jiangsu province and then came to Beijing's CAFA Central Academy of Fine Arts (best school in China) to continue my studies.

Where were you born?

I was born into a large family and raised in a village in the north of Jiangsu province, close to the harbor.

What part of China most influenced your work?

I'm deeply influenced by the fringe, where rural and urban meet, where Chinese culture is suffering great changes full of contradictions because of modernization. I am interested in common villagers left by the new modern life style. There is also the issue of people and their relationship with earth, are also been alienated, from their land, their roots.

How did you first come to Beijing? Can you tell us a story about this?

I resigned my job as an art teacher in Jiangsu and made a performance next to the sea, and left the countryside for good. I came to Beijing to continue my studies and do art works.

What inspired you to start the Walk the Cabbages Series? What is the importance of liubaicai to the Chinese peasantry?

The reason for “Walking the Cabbage” has been changing year by year. Every Chinese person has a memory related to the cabbage. Since I was a child, I've been working in the fields, sowing and harvesting Chinese cabbages and selling them in the big city. In the big cities, people buy and stock up on cabbages for the winter. The liubaicai can be kept for a long time and its the cheapest vegetable in China. It is a sort of identity badge for Chinese people. In the beginning of my performances with the cabbage, I didn't use a leash, I used a red thread which I didn’t hold it in my hand. The thread was attached to my clothes, this represented the connection between the cabbage and I. I started walking the cabbage in Beijing where I was a foreigner, a stranger and used this action to relate to people. The presence of the cabbage was a sort of friend or company. Later, this performance developed more complex and varied meanings.

Where have you walked the cabbage?

All over China, in the cities and in the countryside. It was an ongoing performance. For two years I would walk a cabbage every day, no matter where, I was and it became part of my everyday life. I've also walked the cabbage in other countries, France, Belgium, England, USA, Japan and Korea.

What is the significance of the Mating Season Series?

The Mating Season Series represent the emotional crisis of modern society. It brings out the importance of feelings, transforming hard into soft (hugging stones, kissing knifes). This performance rejects apathy.

Why do you caress such household objects as shovels, bricks, and shoes?

Daily necessities are in close contact with people's lives. I'm aware some people would think the objects I choose are too common, I believe these objects are the most sacred ones; they are directly connected to the way we build our lives. They represent people's labour, but labour without love can result in many problems (see Love in the Big Construction). We must embrace these objects and with the same attitude, we will find it easier to face environment issues and other important aspects in our existence.

Where did the term New Culture Movement originate?

A hundred years ago the intellectuals in Qing Dynasty generated a movement called “New Culture”, rejecting traditional customs and bringing in new and “Westernized” ones. Later on, Mao Zedong also led a Cultural Revolution, once again “culture” is present but this movement was more government-related. Finally, in the early 80s, Deng Xiaoping leaded what was called “the reform and opening-up policy”. Even though these three movements were initiated in different times by different kinds of people (intellectuals, labourers, officials, capitalists and bureaucrats) they have in common their origin, they were started by the elite. The symbol of an intellectual is a book, Mao's red book whereas the red brick symbolizes reform.

Where did you take these photographsfor New Culture and why are the people so keen to hold the bricks, what does it mean for them?

I've taken pictures in the countryside and in the cities in China, since the “New Culture Movement” is happening in a rural and urban context. For them, bricks represent their life, what they do for a living and how they exist in the world, it also shows that they've abandoned labour in the fields and become part of the city culture. They hold the bricks in their everyday life. So when I asked them to take picturesof them holding brick, it didn’t feel in any way strange to them.

Is China building a land of equality for all?

Obviously not equal for all.

What do you feel are the most important issues for China today?

There are many subjects of concern. I think the end of traditional culture, the schism with the past is something that we need to pay attention to. This includes the loss of traditional costume, customs, and is more deeply related to issues such as human rights and ecological issues

[from other interviews with Maya Kovskaya]

What inspires you?

Love, labour and liberation. People who struggle and still maintain their dignity. People who think and care and have the courage to act on their principles. Art that engages real peoples' real lives and provokes genuine emotion, intellectual growth and new commitment. Art that takes place in society and belongs to the public sphere, not just in galleries and before the eyes of elites.

How does it feel to be a young artist from the country in the city? Is that something you have in common with any other artists here in China ?

When I first came to the city, I was shocked by the life here. People worked like machines, squeezed together in subways, on the streets. Life was chaotic and loud and filled with pollution, noise, garbage, crowding, complicated interpersonal relationships, people struggling and striving, sometimes doing anything to get ahead.

I felt this enormous desire brewing in the city's quest for so-called “development.” What especially struck me was the pervasive power of this desire—desire for survival, desire for material, desire for power, desire for fame—propelling people forward and driving them to do all manner of things.

Life in the city is not as simple as life in the country. But while rural life is in many ways much harder than city life (physically), most rural people have fatalistic attitudes towards their lots in life, and so until recently, until the onset of progressive urbanization, people didn't have such pronounced desires, and so in some ways were more at peace.

Like so many rural migrants, I came to the city with a tiny amount of money in my pocket. Although I was lucky to be attending an Advanced Studies program at the Central Academy, I felt an affinity to those other migrants who came seeking their fortunes. The city was so unyielding, and the locals were so filled with prejudice towards migrants. In some ways, Beijing was a very unwelcoming city.

The place I first lived was Xibajianfang before it was demolished (not far from where 798 is now). It was an enclave of migrants, merchants, small-time prostitutes, manual laborers, hourly workers. My neighbors in the courtyard, which was located next to a stinking garbage infested river, included a vegetable merchant couple in one room, 9 petty thieves who lived together in another 12 sq meter room, and an older thief couple who look in apprentices, next to us. I was lucky to have a room all to myself.

Because my family had to struggle to take care of my four other siblings and grandparents, I lied and told them I had a full scholarship. In fact, when I first arrived, after paying rent and buying basic living supplies, I had no other way to survive (unless I chose to join my neighbors in petty crime), but sell some cheap items, like pens and pads of paper, spread out on a piece of cloth on the ground of a pedestrian overpass. I didn't even have the money to buy a pot to cook food in. I ate what I could afford—usually one steamed bun a day. The thieves sometimes shared their vegetables with me. When I finally made enough money to buy a little coal burner, and a pot, I made some rice. At the time I remember thinking it was the most delicious thing I'd ever eaten. But the next day when I returned from class, my coal burner, pot, and 7 oil paintings had all been stolen. All I had left was a head of Chinese cabbage. It was one of the loneliest days of my life. I began to think about what cabbage really means to so many ordinary Chinese people.

My background is something that differentiates me from most of the artists in the contemporary scene. Most artists actually come from cities, or towns, but very few from rural villages. I think most of all my rural background and experience when I first came to Beijing, made me especially sensitive to the plight of ordinary people, and able to work with them as equals rather than treating them as objects of pity or disdain from a safe distance, as some people do. For some reason, in Chinese contemporary art, there is very little work that deals with the everyday lives and concerns of the vast majority of the population—peasants. Anything regarding peasants is often relegated to the category of documentary work, rather than conceptual, contemporary art. The majority here in China, then, is marginalized. In art as in life, these people have little in the way of “discursive power,”(huayu quan) they have no space of their own in the public sphere and when they are represented, it is usually from a considerable distance. Urbanization is treated as a problem of cities, but in reality, the process and effects of urbanization are intimately tied up with the rural situation in China. It is rural people who are building the New China. They are not simply the objects of “development,” they are the ones carrying out the backbreaking labour of it. Ironically, there is little space for them and their concerns in this New China, just as migrant construction workers will never live in the fancy high-rises they build. This isn't just a Chinese problem, it's a problem that I think most of the Third World has faced or is facing as it is transformed.

GAO XIANG CV

born in 1971 in Kunming, China

first a teacher at Yunnan Art lnstitute, then received his Ph.D of Fine Arts from the China Central Academy of Fine Arts in 2008

studies GiorgioMorandi's painting

artworks collected by Shanghai Zhengda Art Museum, China Century Museum, Yong He Art Museum, Ling Sheng Art Institute, Yuan Art Museum, Huangtie Time Art Museum, Yunnan Art Museum, Taiwan 85 Star Art Center, Norway Vestfossen Art Museum Guangzhou Art Museum

Gao Xiang comments on his canvasses the Red Bride Series and their relation to surrealism, December 2012

In your Red Bride Series, the bride is a surrealist apparition larger than life? The artist (yourself) is a tiny dwarf in her hands. Why the strange perspective?

I feel that it is natural and comfortable to draw the bride much bigger than me in the Who is the Doll? series of paintings. Although the perspective is far from real life, but it is very close to my psychological reality.

Are you inspired by the surrealists, or other Western painters?

Yes, I am inspired by surrealists like Paul Delvaux, His works are fascinating, between reality, dream and sexual desire. Also Giorgio Morandi. His works are so spiritual, the still lifes are real objects but they are beyond reality and acquire spiritual and religious meaning.

Explain why red is such an important colour in China.

Red is a cultural totem and represents the spirit in traditional China. Red is also connected to the elements: fire, the sun and thus life. In the Han dynasty (206 BC–AD 220) and Ming dynasty (1368-1644) two important dynasties, red represented the South and the government came from South. Only the royal family was allowed to use red at that time. So, the red became a very special colour and represented power. In the 20th century, red represents revolution and power as well. The Chinese used to love and respect red. We still take red very seriously.

The artist still wears a blue Mao outfit, why is this?

The artist always wears a blue Zhongshan or Mao suit because it represents the officials, those in power. The suit was designed by Sun Zhonshan (Sun Yatsen) and represents Chinese political official style. Many famous figures such as Jiang Zhongzheng, Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping wore this kind of suit. Westerners call it a Mao suit because they associate it with the Great Leader. Before 1980, it was the official wardrobe of all the Chinese. It has a very Chinese feeling about it.

Do you feel that women in China have gone backwards, from feminist Communist heroines to dolls and muses?

I have not thought of this before. From my perspective, this series of works does not seek to an answer but rather to ask a more complicated question. Why does the painter (me) keep asking the question “Who is the doll?” although the paintings show the bride bigger than the artist on the canvass. The painter is not exactly certain of the scene he has witnessed in the painting. In fact, I wonder if I am talking more about the relationship and balance of power between female and male from my own psychological perspective.

What do you think is the single most important factor in Chinese development? What has changed since Maoist times?

Today, I think that the culture factor is the single most important factor in Chinese development. Compared with Maoist times, China is much more open and is developing economic at great speed. But, education and culture are not developing as quickly. China is putting the emphasis on economics and ignoring the culture factor and the value of culture these past thirty years. Now, there are a lot of problems because of this and it is a great pity.

Your work features a curtain, is the curtain signifying life as a representation, “all the world's a stage”?

Because I participated invarious performance projects in Southeast Asia, I used to express my feeling by representing the stage in my paintings. The curtain also provides meaning and feeling.

How did you come to be an artist? Where did you go to school? Where were you born? What part of China most influenced your work?

I was born in Kunming, Yunnan Province. My father, two uncles and one aunt are all painters, so I studied painting early. It was a natural; I started with my father at age ten. From my three to seven years of age, I enjoyed drawing and paintings on the wall. I could only reach the wall when my parents went to work in the factory. They were angry and punished me but kept drawing this kind ofwall fresco as soon as they went out. From 1990 to 1994, I studied at the Yunnan Art institute and became a teacher in the same institute when I graduated. From 1997 to 2000 and 2003 to 2008, I studied oil painting at theChina Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing where I did myMA and PhD. I was very influenced early on by the natural landscape ofYunnan, Chinese traditional literati paintings and the early Buddhist Silk Road frescos of Dunhuang and Yungang.

CHANG LEI CV

born in Jinan Shandong

rock musician turned artist

painter, photographer

born 1977

exhibited at “[UN] forbidden city” MAC RO (Rome), Wall art Museum China, “Breathe” A Shandong Art Museum

personal music album The Setting Sun

penned poem- novel Mr The Setting Sun, Finished

main character the elephantor “Xiang » in Chinesemeaning appearances or the Communist party

often features himself in his work

Chang Lei on his Mirror images series and on being one of a pack of China’s rock stars converted to an artist, like Zuxiao Xuzhou and others.

How did you come to be a painter ?

I liked painting when I was little and still love it now. A few years after my university studies, I started to be a part of the rock and roll music scene. It is a pleasant memory.

Your series Mirror Images is a series of canvasses with calligraphy by Chinese presidents and then, a representation of a person or an elephant below? What does this mean?

“Inscription” or calligraphy in Chinese history is a cultural phenomenon. It is a symbol of power in most cases, it is also a symbol of “class” and “hierarchy”. If an inscription is the calligraphy of people in power, it takes on a political meaning. Take “China Mirror Images- New Men with Four Merits” for example. Deng Xiaoping writes in his own hand that one must “select and train successors with idealism, morals, culture and discipline for the great proletarian revolutionary cause”. He wrote this phrase for the Chinese Young Pioneer League on its 40th anniversary in 1980. He asks the children of China to become the new champions of the proletarian revolutionary cause. People were forcibly brainwashed and forced to accept his ridiculous ideology. This kind of calligraphy became a sort of command in the form of a political slogan. But what was the reality? It turned out to be a total disaster after Deng's economic reform, the lagging behind of education, the rigidity of thinking, high tuition rates, inequality of education, lack of resources and corruption in the education system. Children brought up in this environment became cynical, demoralized, furthermore they were uneducated, leading the society to the verge of collapse. The elephant in China Mirror Image ridicules Deng's inscriptions. The smoking kid in the painting makes the viewers panicky and anxious. Is this the future?

Another example is “China Mirror Image-Long March Poem”, written by Mao Zedong after the Long March. Mao treated people brutally and cruelly, even those who had fought bravely alongside him, even the youngest soldiers who died anonymously. Some are disabled for life and have little living support. So the Long March poem appears to be even more ridiculous and cruel. Mao disdained the world and was only a “smiling” Peron, a tyrant. The elephant is a homonym for “appearances” or “reality”. You can never know if it is what you know is real. It could all be your imagination.

Tell us about propaganda. Are you talking about how propaganda influences people's lives? What does the elephant as an animal mean in your work? Do you think China will evolve out of communism and liberalize?

Political propaganda is the norm for a totalitarian country. China is not alone. Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Soviet Russia and Kim Jong-Il's Dynasty are all the same. Political propaganda not only affects people's life, but also makes people serve for the interests of the rulers, the ruling party, the state and interest groups. Like the elephant in the painting, we can never know the damage caused by the political policies, even though we can feel hurt. In China, we are all blind when we face housing, medical service, insurance, education, laws, taxes, food, media, economy, environment, history, culture, politics and so on. All we can do is to imagine and misunderstand. We are the blind, the system is the elephant. Elephant is pronounced as “xiang”, exactly the same as “ reality”. So here the elephant is a paronomasia or homonym. China is the biggest country in the small group of Communist countries. We have been living under the hypothesis, the illusion of Communism. China is lingering in the uncertainty, Chinese systems are transmigrating. We are in limbo.

What do you think the impact of Mao was on the country as a whole, good or bad?

Mao ruined the Chinese mainland. The masses lived in dire poverty for a hundred years. IT WAS A DISASTER!

WU JUNYONGCV

Wu Junyongwas born 1978 in Fujian

printmaker, painter and animation expert

Beijing China Academy of Art graduate

Lives and worksin Hangzhou, China

exhibited at F2, Arario, Hanart as well as in museums such as “The Dismemberment of the Power of Flash”, Shanghai Museum of Contemporary Art, , MY CHINA NOW, Hayward Gallery, London, participated in The Toronto Reel Asian International Film Festival, RED HOT - Asian Art Today from the Chaney Family Collection, Houston Museum of Fine Arts, Yelow Box, Qingpu, Gong Chan No1, Shanghai Duolun Museum of Modern Art, Shanghai

Wu Junyong answers questions about his papercut animation, December 2012, interview by Pia Camilla Copper

How did you come to be an artist? Where did you go to school? Where were you born?

I was born on the cost in Fujian. I studied at the Central Academy in Hangzhou, a lakeside town, major in printmaking. Beijing is like a big stage. I started in a village, then moved to a regional city, then moved to Hangzhou – which is quite a big city – and now I’ve moved to Beijing, an even bigger city. It’s fun here. You can meet all different kinds of people: smart people, stupid people, over the top people, some crazy people. All kinds. And you can see that everyone’s performing – I’m performing too. It’s just that we all have a different performance.

Your work often feature men in dunce caps, reminiscent of the shamed intellectuals of the Cultural Revolution? Are these men politicians?

They are petty and foolish people. Presumptuous, self-righteous puppets. They flash before your eyes like the creatures Alice in Wonderland meets in the rabbit hole as my friend Gao Shiming says. Are they on parade? They are like Chinese politicians or politicians all over the world. The absurdity of reality leads me all the more to allegory, I am a narrator between reality and imagination, a world of illusions.

What about the hat?

This year the answers will probably all be the same, but they’ll be different from the answers last year, because the meaning of the hat is always changing. So it might have started with the idea of ‘daigaomao’ – to wear a tall hat – which in Chinese culture means that I might praise you and be very over the top in that praise. I give you a tall hat to wear, but in fact the praise and flattery is all false.

In China everybody’s constantly flattering each other. In the paper, you can see the government praising itself, praising China, praising the Chinese people. Chinese friends, when they’re together, are the same – just praising and flattering each other. It’s a big joke! So the hat has this kind of meaning.

Your work also features stork, horses, dragons, all symbolic? Why the use of these fantasmagorical animals?

I am interested in expressions “to call a stag a horse” (to confuse right and wrong). To me, it is not important what one says when he calls a stag a horse, but the new “species” that derives from the called—a horse with deer horns becomes a public scene, nonsensical as it might seem. Animals often have a kind of symbolic status. They represent things. So for example a dragon has a lot of meaning in China – it’s supposed to fly in the sky, to be powerful. But then I’ll often have dragons falling from the sky, or even being cut up – about to die, sapped of their energy.

Can you explain the process of your video making? You first make papercut figures, which you then film?

I was very influenced by folk art as I grew up in a village.

What do you feel is the most important issue for China in the future?

I feel my films are melancholy. You can feel the direction of the characters is probably not good – is probably getting more and more dangerous, more and more corrupt. So you start to wonder why, and what it is they’re actually doing. I don’t really know what the audience is thinking, but a lot of people say they can sense that mood. This is the mood in China today.

LU FEIFEI CV

born in 1980 in countryside

was working in a café when she met the Gao Brothers

lives in Beijing

actress and muse of Gao Brothers for their sculpture, their photographs

has written and appeared in her own film

participated in such shows as « Post-70s generation », Beijing 798 art festival , “Change of Dragon's body” , New York China Plaza Art Space, “UN-Fordidden City”, MAC Museum (Rome)ez

Why the story of Zhuyuan?

The Zhuyuan Township in the Yimeng Mountains, has no landscape “neither mountains nor water”, only a human landscape. This is one of the reasons I decided to leave there at fifteen years of age. But it is after all, is where I was born, my parents, my brothers and my sisters are still living here. So, although I later moved to the capital as a freelance writer and artist, my dreams often return to the shadow spirits of Zhuyuan or the Bamboo Grove Village. Home for the annual Spring Festival holiday, my memories are still intense, and I am full of nostalgia and sadness for Zhuyuan where nothing ever changes. My little town has family planning. After the birth of a brother and four sisters, I still do not know why parents insisted and ran the risk of being punished severely when they gave birth to me. I was only five years old when they decided to untarnish my name and have me registered as a legitimate child. A very special fate. One cannot avoid one’s own beginnings. This beginning, unknown child, unregistered, unnamed, affected everything, the way I look at life and society, art, literature, and even politics.

I shot the Zhuyuan series in my hometown in 2009. The image was of two girls, a niece named Xuan Xuan, and her classmate Zhi Zhi or Wisdom. Both of them have a brother in the countryside, if the first child is a girl; one is allowed to have more children. But patriarchal custom persists, the girl child is not the favoured one at home. I deliberately chose to shoot the photograph with a government slogan as background. The girls always stand in front of the slogan oblivious. The way the culture thinks and the way society thinks are at odds with government policy.

In democratic countries, the flag is a symbol of glory and dignity, the symbol of the nation, in a country where people do not have the right to vote, the national flag represents the government’s will and power. The flag as well as the “One Child in Zhuyuan” slogan signify the same thing. The girl, the flag, the ice, the trinity; the girl, the flag, the haystack is very important. Like the girl, the situation of women remains unnoticed. The situation of the girl child is similar to that of the Chinese people, helpless, coerced by power, without freedom or power to choose.

I am also concerned with underprivileged women more unfortunate and their social status and problems, although I am not a feminist. I think that the consciousness of human rights is inherent to the female. Feminism is like human rights awareness. So, I hope people will better understand the situation of women and of China through my works. From an aesthetic point of view, they will also understand the lone girl, on the icy haystack. After all, the expression of social consciousness is also art which represents an individual social and political consciousness, that of the artist.

ZHANG HUAN CV

Zhang Huan needs no introduction

performer, painter, photographer, opera director (Semele in Toronto, and Brussels)

invented the ash painting and the ash Buddha

most beautiful male performance artist in China

born in 1965 in Anyang, Henan

lives and works in Shanghai and NY

graduate Central Academy Fine Arts, Beijing, China(93)

Solo exhibitions at Rockbund Museum (Shanghai), Louis Vuitton (Macao), Shanghai Art Museum, Museum of Contemporary Art Taipei, Pace Gallery (Beijing), PAC Museum (Milan), Ullens Center for Contemporary Art (Beijing), Gallery Haunch of Vension, Nikolaj Copenhagen Contemporary Art Center,Asia Society (NY), Tri Postal, (Lille), Kunstverein Hamburg, Deitch Projects and so on

Zhang Huan’s « Family Tree » has been lent to us by a Montreal collector for this show. The work was done in 2000 in New York.

Zhang Huan commented at that time:

“I have been feeling pain on the left side of my chest for over a year, which lately seems to have gotten worse. I sense an ill omen and am afraid that something unpredictable might happen.

When a mother squeezes out the last bit of her energy, a new life eventually emerges. There are numerous events in our lives over which we have no control.

More culture is slowly smothering us and turning our faces black. It is impossible to take away your inborn blood and personality. From a shadow in the morning, then suddenly into the dark night, the first cry of life to a white-haired man, standing lonely in front of window, a last peek of the world and a remembrance of an illusory life.

In my serial self-portrait I found a world which Rembrandt forgot. I am trying to extend his moment.

I invited 3 calligraphers to write texts on my face from early morning until night. I told them what they should write and to always keep a serious attitude when writing the texts even when my face turns to dark. My face followed the daylight till it slowly darkened. I cannot tell who I am. My identity has disappeared.

This work speaks about a family story, a spirit of family. In the middle of my forehead, the text means “Move the Mountain by Fool (Yu Kong Yi Shan)”. This traditional Chinese story is known by all common people, it is about determination and challenge. If you really want to do something, then it could really happen. Other texts are about human fate, like a kind of divination. Your eyes, nose, mouth, ears, cheekbone, and moles indicate your future, wealth, sex, disease, etc. I always feel that some mysterious fate surrounds human life which you can do nothing about, you can do nothing to control it, it just happened.” (Zhang Huan website)

GU WENDA CV

Born in Shanghai in 1955

1980s and 1990s first generation of Chinese artists

graduate of Shanghai School of Arts

graduate of Central Academy of Arts (Hangzhou), professor there from 1981-87

expatriated to the USA

selection committee PS1 Musuem (NY), Chicago Art Institute

Works shown in Taiwn, China, Singapore, Korea, Indonesia, Malaysia, Israel, Australia, Norway Germany, Norway, France, Russia, Canada, Korea, Mexico, Switzerland, Indonesia, Turkey, USA, Polnd, Brazil, South Africa, Sweden, Israel, Australia, to mention a few places began his fifteen-year ongoing global art project entitled United Nationsone million people from all over the world have contributed their hair to this art project

Michael K. O’Riley’s called the United Nations project “... a kind of universal tea house, a place where many cultures can assemble and transcend their national differences”. Gu Wenda American flag, UnitedNations project, made of woven black hair, was commissioned by a Montreal collector who lent it to the show.

HUNG TUNG LU

Born in Taiwan in 1968

A Tawainese artist who moved to Beijing in 2000

MFA Taiwan University

involved in computer digital work, holograms

interested in the virtual and the spiritual plastic HUNG dummies, mass-produced religious icons, artificial flowers, and electrical lighting

has invented a manga figure resembling Padmasmbhava Buddha and Svara

Buddhist adept

elaborately tattoed with a Buddha of his own design

has exhibited with Tang Gallery, Osage Singapore, Hanart HK, at MOCA Museum and

Duolun Museum (Shanghai), Fuori Biennale (Vicenza), Denver Art Museum,

Busan Biennale (Korea),Taipei Fine Arts museum among others

Where were you born? Where did you go to art school? How did that influence you? Why did you move to Beijing?

I was born and grew up in a coastal village in central Taiwan, and in high school, I became fascinated withRenaissance art. I subsequently was accepted as an art student at Tainan National University of Fine Arts.

My early art education was more focused on technology and training as an artist . It was only in graduate school, that I became interested in personal creation.

I haven’t “completely” moved to Beijing, I am currently btween Taiwan and Beijing, where I have my studio. I did this not simply migrate from a place to another place, but to expand the scope of my own life. In Beijing, I found roots because my creation needed experience and stimulation.

Your works Padsambhava and Svara are Buddhist in nature, are you a practising Buddhist?

Your Buddha creation has become iconic, what inspired it?

I come from a traditional Buddhist family, monasteries, as a Buddhist growing up, were a very important part of my personal life. This cultural environment, traditional Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianismin Taiwan, has stopped unimpeded development. We have a fairly high degree of religious culture, a pluralistic dsociety, a variety of different faiths than can coexist or become fused. This part of Taiwanese daily life, this cultural background is very strong and naturally became one of the sources of my inspiration.

Are you trying to create a meditative space with these hologram works?

I hope personally that that is one of the goals reached of the artistic creation.

Did you draw the tattoo of Buddha you have on your own back and where did you get it tattoed?

The tattoo image on my back is the image of Padmasambhava, the Buddhist Tantric figure from Tibet, widely known as the second Buddha. This tattoo is from Taipei, done by Taipei’s most fame Tattoo master – designed by me.

Where are the most sacred Buddhist sites in the world today?

In my view, exploring and pursuing various religions, or variety of spiritual beliefs, and eventually, everything will return to the heart itself. I think the heart is the most sacred of shrines within which to practice the self. The heart because it will have its impurities, the presence of the impure.To return to one’s nature, people must first cultivate themselves, and then pursue selfless, pure goals.

HE YUNCHANG CV

born in 1967 in Henan

painter, performer, photographer, sculptor

graduated from the Sculpture Department of Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts in 1991

works and lives in Beijing

ultimate performance artist

believes body is his instrument, unafraid of physical duress

almost a punk, rebel

always representing himself, he considers it a panaceato dictatorship

believes artist expresses will of individual in a repressed state

has exhibited and performed at the Galeri Nasional Indonesia in Jakarta, Pace Wildenstein gallery in Beijing, the Seoul Museum of Art, the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, the Ullens Centre for Contemporary Art in Beijing, Urs Meille Gallery, the Guangdong Museum of Art, the Liverpool Biennale, The Albright-Knox Art Gallery in New York, and the Shenzhen Art Museum to name a few

What is the idea of One Meter Democracy ?

It is the opposition of an individual against the state, proven physically. I had a 0.5 to 1

centimetre deep incision cut into the right side of my body, stretching one meter from his

collarbone to his knee. A doctor assisted in this procedure without anaesthetic. We held a

“democracy-style” vote, using the asking twenty people to vote for or against. The final tally was 12 votes for, 10 against and 3 abstaining, passing by two votes. Some people were shocked. But

I used my body in this process.

What is the idea behind Ai Wei Wei swimsuit?

I stood with many people naked. In China, they think naked is pornography. Yet there is lots of pornography. But when it concerns politics, they often call it pornography too. Wearing theface of Ai Wei Wei, imprisoned for 81 days was a performance, art opposition to politics.

Like Thunder Out of China, Arsenal Montreal, Division Gallery, Toronto, January 2013-July 2013

邱 节 韩冰 艾 未 未 常 磊 谷 文 达 鲁飞飞 吴俊勇 洪 慧 高翔

张 洹 何云昌 戴光郁

Cang Xin Chang Lei Dai Guangyu

Gao Brothers Gao Xiang Gu Wenda

Han Bing He Yunchang Hung Tunglu

Lu Fei Fei Wu Junyong Zhang Huan

with the launch of Ai Wei Wei’s book Ai Wei Wei-isms

Preface

Chinese artists have always been considered “zhishifenzi” 知识分子, “men with thunder and lightning at their heels”. They have always been the critics, the moral safeguards of society. Restrained yet spurred on by dictatorship, artists in China have never wavered, insisting on talking about the real issues such as massive urbanization, the one child policy, the legacy of Mao, the overwhelming burden of propaganda on people’s lives, the imprisonment and exile of dissidents such as Ai Wei Wei. Others have decided to go beyond politics, and address issues of spiritual fulfilment and love. Perhaps this ever so subtle shift is part and parcel of the modernization China is undergoing, the artist themselves have changed, focusing inward to a new reality, the relaity of the self. This exhibition attempts to give a bird’s eye view of the Chinese contemporary art landscape, a glimpse into what artists or as they used to be called « the literati »are thinking and feeling in the Middle Kingdom.

In the past ten years, China has undergone transformations more overwhelming than twenty Western-style « industrial revolutions ». The Confucian family structure has been dismantled, Buddhist doctrine has been let go, old architecture and temples have been bulldozed to make way for a unstable future, an edifice built too quickly and structurally unsound. Even the essence of the original Communist ideal, that of a people’s republic seems to have been lost, making way for a capitalist/Communist mélange, a breeding ground for corruption, inequality and injustice.

In the aftermath of the Sichuan earthquake in 2009, Ai Wei Wei, criticizing the flimsy constructions of schools that left hundreds dead, many children; installed a wall graffiti at Documenta made of children’s backpacks that spelt out: “She lived happily on this earth for seven years.” His statement has far reaching implications, questioning the state’s responsibility in the disaster, endangering himself in the process (his online list of the dead leading to his incarceration) and daring to make a political statement using art. Ai Wei Wei’s book of changyu or proverbs, the little black book, are to present-day China what Pascal’s Pensées and Voltaire’s Lettres philisophoques are to Europe.

Other artists are just as bold. The Gao Brothers’ Miss Mao, which parodies the “Great Leader” representing him as a young voluptuous girl with a long braid and voluptuous breasts, has been forbidden in China. Several Miss Maos, or Mao xiaojie, also a derogatory term referring to courtesans and prostitutes, have been confiscated en route to international exhibitions. The Gaos are artist dissidents, a new breed born in the post-Mao era. Criticizing Mao is still paramount to treason, fifty years after the birth of the PRC, twenty years after his death. Miss Mao is to China what Warhol’s Brillo Broxes are to America, a reflection of the subconscious of a nation, subliminal perception.

Chang Lei, a former “yaogun” or rockstar is also not of the faint-hearted. His “Animal Farm” photograph has also never been exhibited in China. The Forbidden City features as a gigantic Noah’s ark, with all of China’s Communist leaders and army generals watching an unreal scene taking place in front of them on Tiananmen Square, a strange meeting of animals, seemingly chaotic and agitated, with Chang Lei’s naked body as the center of depiction, his hands held over his ears, like in Edward Munch’s scream. Animals tend to gather when there is a storm coming, unknown chaos and uncertainty, revolution. Chang Lei’s dreamlike digital creation is ominous.

Chang Lei’s series on propaganda, featuring pictures of young children next to the calligraphy of Maoist leaders, Deng Xiaoping through to Jiang Zemin, points to the impossible weight of propaganda, shaping generations of people and molding them forever.

Qiu Jie’s “Woman and Leader” as well as “Two Swallows” points to the humorous side of “political pop”, growing up with Marxist-Leninism and loving/hating it. His large scale pencil drawings called dazibao or “propaganda posters”set the scene for a childhood on the Yangtze, traditional life in the teahouses, gardens, of old Shanghai, echoes of the past with acrobats, majiang games and dumpling vendors but with Communist heroines lording over it all, such as the femme fatale or the woman electrician. The backdrop to his childhood reveries and life are the sleeping giant, politics.

Wu Junyong’s video “Cloud Nightmare” is a masterpiece of a master paper cutter, the desuet Chinese art. Yet he uses the most cutting edge medium, video to make these characters come to life. Wu’s characters are brainless politicians, spouting useless propaganda masqueraded as Chinese mythology. They “call a stag a horse” as the Chinese say and the stag, appears and re-appears, a motif in this dream sequence. The men, who look like the Communist party cadres, convened at the People’s Congress, advance like blind men leading the blind. They sit on wobbly palanquins. Wu’s dragon is on fire, a taboo in old China where dragons are always considered immortal.

Lu Fei Fei’s young girls in her photographs, are a mirror of her own experience. She was one the many “elder sisters”, undocumented children, unregistered either as residents or in school because their parents desired a boy. She denounces a cultural practice that has made her obsolete.

As for He Yunchang, Ai Wei Wei’s clique, his performance using his body as a tool to test democracy speaks for itself. The incision practiced on his body, one meter for democracy, voted on by friends, is chilling and very real. The scar is still visible years later in “Ai Wei Wei bikini” in which he poses with nude models, all wearing the dissident’s face on their private parts. ‘The government opposes pornography and politics, why no do both?’ the artist states.

Dai Guangyu is also part of the first generation of Chinese artists, the Chinese “new wave”, who started creating around the summer of 89. A calligrapher and poet, his work bring the traditional aesthetic into the contemporary realm. “His Landscape on Ice”, shanshui and fengshui are part of a performance he did in Germany and China, reminiscent of the technique of the Buddhist and Taoists who use water to paint ephemeral poetry on the stone slabs of temples and palaces. Dai Guangyu’s ink paintings on ice, will disappear when the spring comes, creations reflecting the impermanence of sensorial experience.

Cang Xin, one of the founders of the East Village with Zhang Huan and Rong Rong, the first artist squat outside the Yuanminyuan palace, has never been one for too many words. As an shy art student, he found it difficult to communicate and instead decided to start a series of works called “Communication” licking things with his tongue. If he could not speak, he felt, he must enter into some sort of dialogue with the universe or people.

Later, his work assumed a shamanistic side. Cang Xin decided to posit himself as the shaman, intermediary between the universe and man, the ultimate role for the artist. In doing so, he also re-asserts the power of the individual in a society where all egos are crushed to make way for the collective consciousness. Cang Xin, wears an amulet of his own face, his shaved head, distinguing himself as an artist

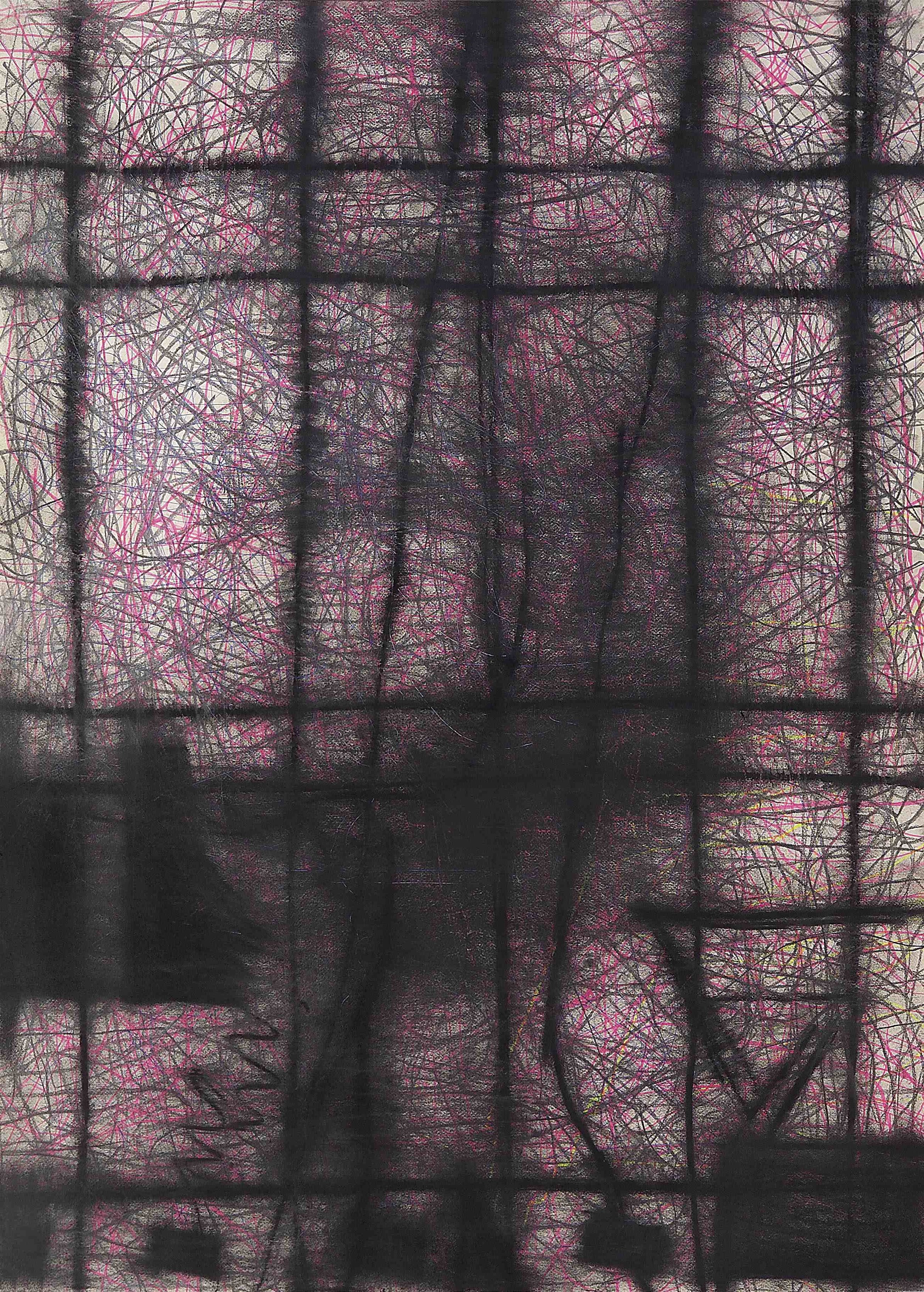

His giant Chinese-style scrolls in pencil are a self portrait, the artist becomes a demi-god, sitting cross-legged, in a Buddhist position, on the back of a qilin, a Chinese unicorn (identified by its scaly skin, dragon’s head), symbol of happiness and good fortune and a tortoise, symbol of Chinese longevity.

In Han Bing's "New Culture Movement" photo series, laborers, old people, and even school children, stand in front of the camera, like peons in a chess game, a red brick in their hands reminiscent of the little red book.

It is ironic that these villagers still believe in the Maoist dream of a brick house for all. In a China where glass and steel skyscrapers have overtaken the landscape, the rural working classes are lagging centuries behind the city dwellers. Han Bing did not set up these photos, the people he took photos of, are plainly and almost naively speaking of their dreams and aspirations, clinging to an ideology and a culture that has been left behind in the rush for modernization. They have no notion of what the modern era holds.